The typical household income of African Americans today is 58.6 percent that of whites. But African Americans’ average household wealth is just 10.1 percent that of whites — a circumstance that Richard Rothstein, distinguished fellow of the Economic Policy Institute, said is “almost entirely attributable to federal housing policies from which African Americans were excluded.”

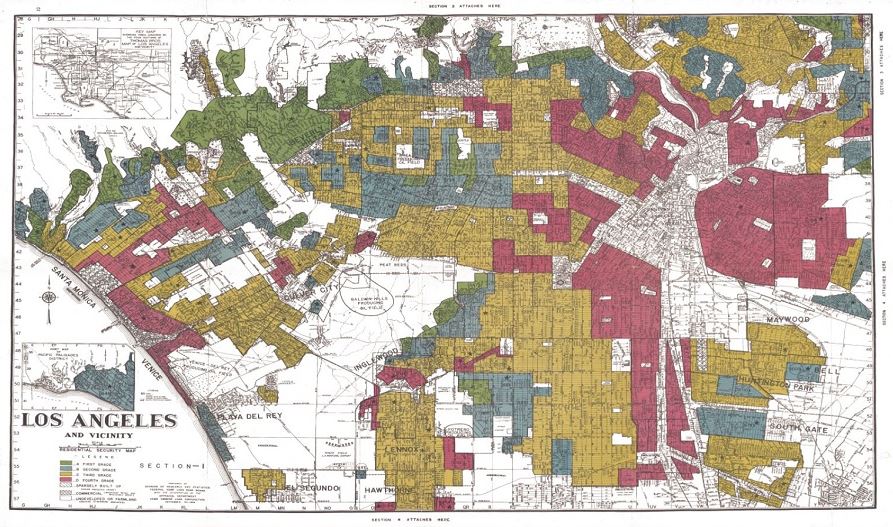

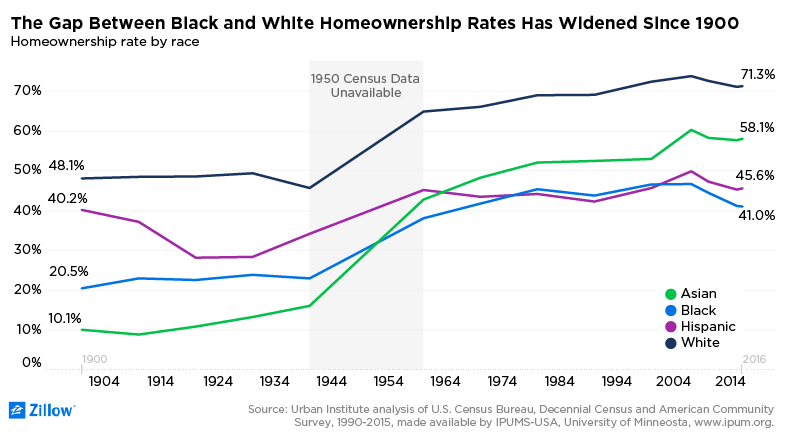

“Throughout the mid-20th century, African Americans were prohibited from purchasing homes in suburban areas,” said Rothstein, who’s also senior fellow emeritus at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. They’re strong words, and unfortunately, the paper trail of history proves them right. The gap between black and white homeownership rates has been consistent for more than a century.

A ‘shield of honor’

For years, cities banned whites from selling homes to blacks in certain neighborhoods using racial zoning ordinances. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down such ordinances in 1917, after which restrictive racial covenants took off. They were essentially private agreements that did the same thing.

Restrictive racial covenants became so fashionable that in 1937, a national magazine “awarded 10 communities a ‘shield of honor’ for an umbrella of restrictions against ‘the wrong kind of people,’” according to a 1973 publication by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “By 1940… 80 percent of both Chicago and Los Angeles carried restrictive covenants barring black families.”

Then, in the midst of the Great Depression, two agencies that were created to stabilize the country’s devastated housing market adopted racist practices that kept blacks from participating in a housing boom that rocketed white homeownership from 46 percent in 1940 to 65 percent in 1960.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) played a major role in keeping minorities out of certain housings:

- Minority loan restrictions. The FHA recommended restrictive covenants that barred minorities from receiving federally backed home loans. (The Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that such covenants are not enforceable.)

- White-only suburbs. The agency subsidized lending for the development of suburbs, with the stipulation that the homes be sold only to whites.

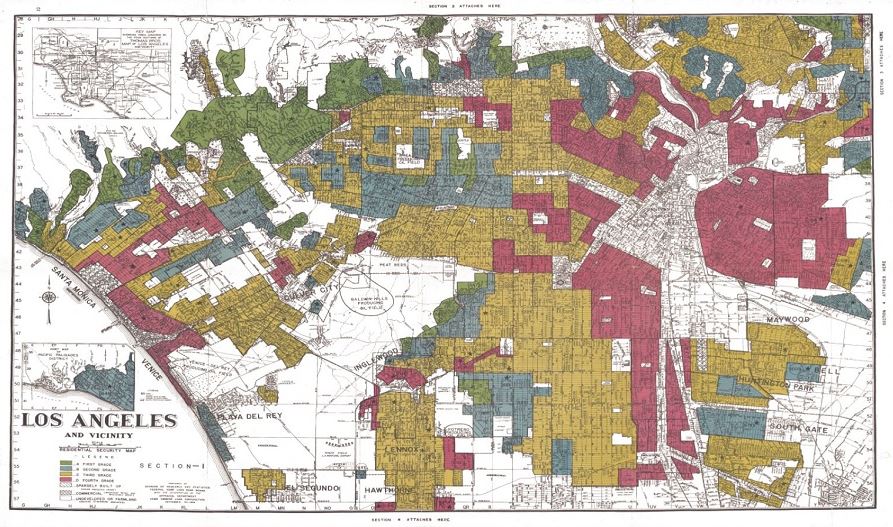

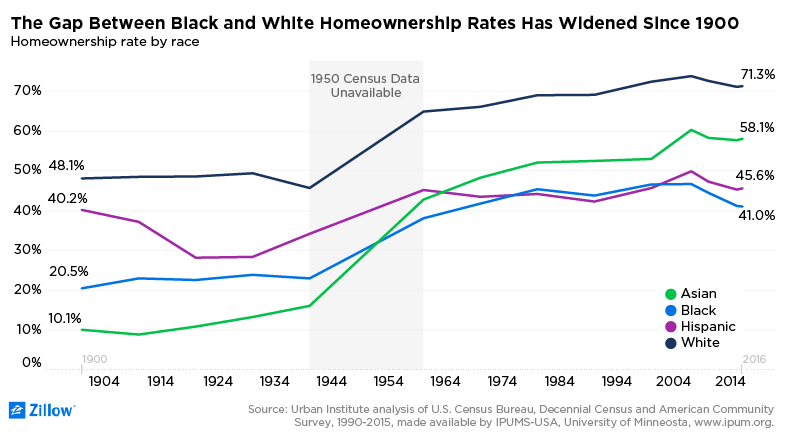

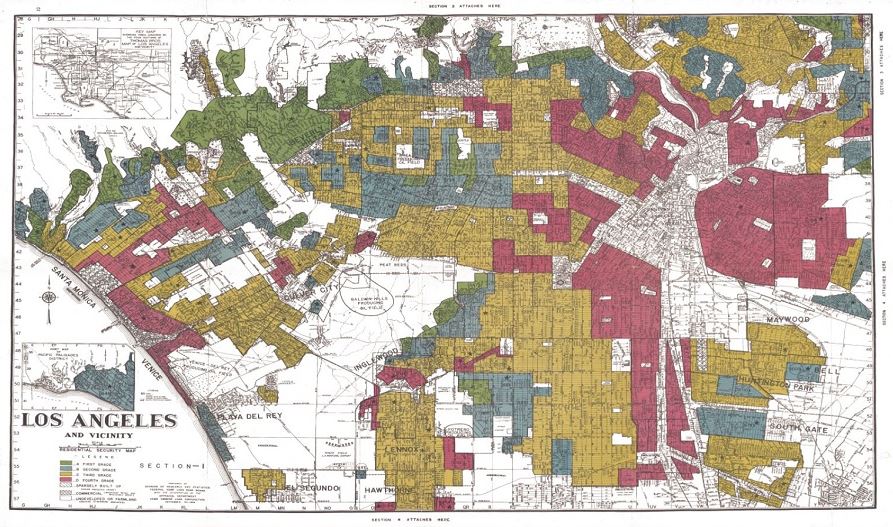

- Redlining. The FHA discouraged lending in predominantly black neighborhoods.

A 1939 redlining map of Los Angeles from Mapping Inequality, a project of four universities led by Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly and others. Click on the map to link to the full project.

Redlining was based on evaluations from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), another agency formed during the Great Depression to stabilize the housing market. HOLC was tasked with assessing the risk of lending in neighborhoods across the country, and it coded communities that were primarily African American red — for high risk.

It believed property values would decline if blacks moved into a community — even though there was no evidence of that. “In fact, the opposite: Property values increased. Because of the reduced supply of homes available to African Americans, they were willing to pay more,” said Rothstein, author of the new book, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

The private sector played a part: “Real estate agents would not show African Americans homes in all-white neighborhoods, banks would refuse to grant African Americans conventional mortgages, and contractors could not get financial backing to construct homes for African Americans in white neighborhoods,” said Coty Montag, deputy director of litigation at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

There were also personal assaults, sometimes literally. “White homeowners would actively discourage African Americans who tried to move to their neighborhoods,” she said. “In some areas, there would be violence or other ways of discouraging new black neighbors.”

Incarceration plays a role

By the time the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it easier to challenge housing discrimination, much damage had been done to black families’ wealth and real estate prospects. That legacy is compounded by modern problems.

One example is the financial impact of mass incarceration, which as of 2001 meant one in six black men had done time. When they get out, these men can rarely put their name on a lease, because that requires a criminal background check. Their wives often build credit histories and apply for mortgages alone, even when they’re married with families.

The impact can be huge for much smaller criminal violations. Some people who were jailed for misdemeanors but did not pay the accompanying fees can end up with a bench warrant on their records, said Rolf Pendall, an institute fellow at The Urban Institute.

They also miss work while they’re in jail, even if they’re not indicted. Those are real issues for people who were swept up in New York’s stop-and-frisk phase, and who live in communities with a big police presence. “All those things combine in a pretty toxic way,” Pendall said.

Modern problems and solutions

For the reasons above and for many others, blacks are turned down for mortgages at twice the rate of whites. That’s not counting African Americans who do not even bother to apply for home loans.

“Far fewer applications are submitted in black neighborhoods relative to white neighborhoods, even those with similar income levels and homeownership rates, whether because of reduced exposure to availability opportunities or early discouragement,” said Zillow Senior Economist Skylar Olsen.

Mortgage application figures are available through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975, which was meant to help regulators determine if lenders are serving their communities’ credit needs. HMDA requires lenders to collect information about borrowers’ race, ethnicity, gender and age.

Similarly, the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (CRA) encouraged banks to have a greater presence in underserved parts of their communities — places where payday lenders and pawn shops often outnumber bank branches. Some say that regulatory encouragement helped stoke the recent plague of predatory lending that helped spur the housing crash and the Great Recession.

Whether CRA played a role or not, predatory lenders did disproportionately target minority communities with their unscrupulous loans. “We just went right after them,” one former loan officer told The New York Times.

Those areas have had the toughest time bouncing back — and they’re not just poor areas. Prince George’s County in Maryland, the country’s highest-income majority-black county, saw half the loans on newly constructed homes from the 2006 and 2007 housing boom go into foreclosure, The Washington Post found.

Some lenders steered African Americans and Hispanics with good credit scores toward subprime or predatory loans, Montag said. A former Justice Department attorney, she helped litigate a Department of Justice case against Wells Fargo for such steering that led to a $234 million settlement.

Solutions abound, from educating people about credit histories and homeownership, to creating new mortgage products, to finding new ways of scoring credit that take into account people with different types of income and backgrounds.

Some go so far as to say that the only real way is to even the economic playing field.

Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, senior fellow of the Racial Wealth Divide Initiative at the nonprofit Prosperity Now, argues that to gain more than 50-percent homeownership, minorities need the types of progressive economic programs that whites enjoyed in the ’40s and ’50s. Minorities were explicitly left out of those programs.

Asante-Muhammad co-authored a report that found that if current trends continue, median white household wealth will increase by more than $46,000 to $186,900 by 2049, while Latino household wealth will grow to a median of $9,700 and black household wealth will decline to $1,700.

If white wealth remained stagnant and black and Latino wealth continued to grow at the higher rate it did between 2013 and 2016, it would still take black families 242 years and Latino families 94 years to gain parity. The report recommends, for example, reforming the U.S. tax code “to ensure households of color also receive support to build wealth.”

“It’s not just for racial justice,” Asante-Muhammad said. “If you have people with such unequal, low income and even lower wealth households, you’re not going to have that booming American economy any more.”

When Ta-Nehisi Coates, a national correspondent for The Atlantic, makes the argument for leveling the playing field, he points to the impact of long-standing forms of housing discrimination. “Identifying the victims of racist housing policy in this country is not hard. Again, we have the maps. We have the census.”