Asians and the Homeownership Divide

Asians have been deeply affected by discriminatory housing policies from the 20th century, including redlining and restrictive racial covenants. Many Asian Americans, especially first-generation immigrants, face cultural barriers to the U.S. style of lending and home buying.

Christopher Kui remembers a time years ago when lenders did not want to offer special loan products or financial education for Asian Americans, the way they sometimes do for other minority groups.

The mortgage denial rate was about the same for Asian Americans as whites, which lenders saw as proof that there was no discrimination against Asians. But Kui, who is the retired longtime executive director of the nonprofit Asian Americans for Equality, saw mortgage lending abuses in the Asian-American community. Borrowers were charged too much for loans and were pushed into “non-conforming” programs that charge more but do not require a credit check.

Kui challenged the banks to check their records for the size of down payments their Asian-American borrowers were making. “They saw 25- to 30-percent down payments,” he said, indicating these customers were not traditional, but also not deserving of high-cost loans. “I said, ‘You’re not serving the whole market.’”

Parity, but not full opportunity

Like all minorities, Asians have been deeply affected by discriminatory housing policies of the 20th century, including redlining and restrictive racial covenants. Those laws and regulations prevented many racial and ethnic minorities from buying in suburban areas, from buying certain homes from white people, and from being able to get a loan in minority-heavy neighborhoods.

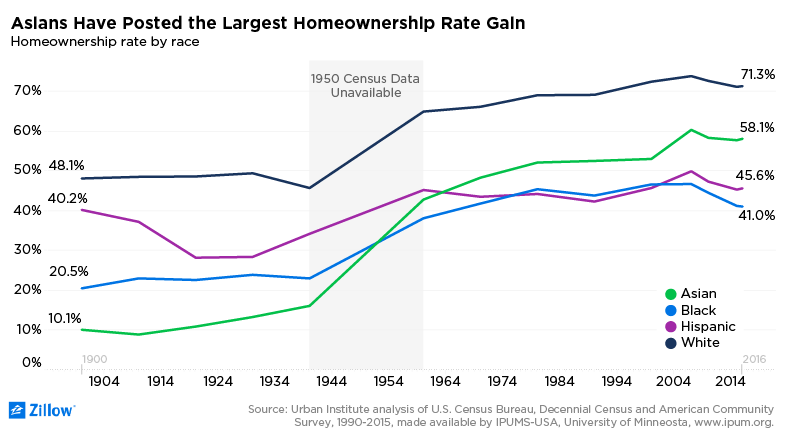

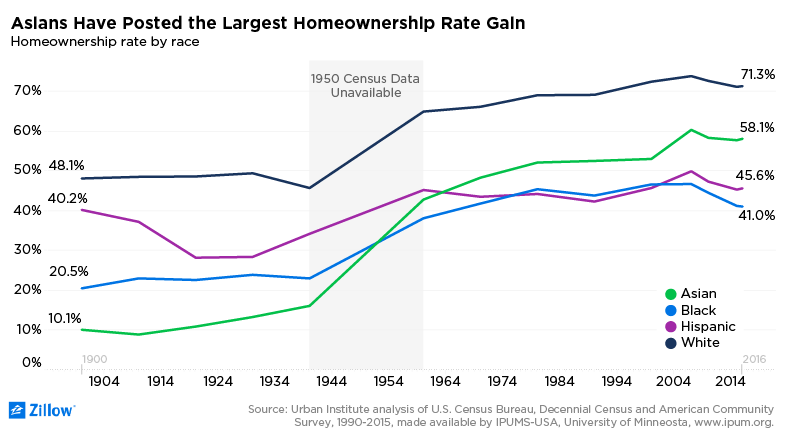

Asian Americans persevered, boasting the highest homeownership rate of any single minority group beginning in 1970. The share of U.S. homes they own (4.4 percent) is now almost even with their share of the overall U.S. population (5.6 percent) — despite the fact that many of them live in coastal cities where renting is popular.

“For some reason, we like to live by the water,” joked Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, assistant director of UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center. That means high-cost cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle and New York.

“As a result, they may not be able to afford the purchase of a home,” she said.

Despite their gains as a group, many Asian Americans, especially first-generation immigrants, face cultural barriers to the U.S. style of lending and home buying. It can be difficult to specify their economic challenges, because, like any group of people, Asians are not homogeneous: They come from dozens of countries with vastly different national incomes and cultural histories.

Still, some financial habits hold true across more than one group. For example, Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese immigrants often share ownership of homes with their extended families, said Alexander von Hoffman, a senior fellow at the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

In addition, Zillow Group’s Consumer Housing Trends Report 2017 shows that 22 percent of Asian buyers receive help from family and/or friends when they’re putting together a down payment.

Missed opportunities

“The advantage of extended family networks is that few seemed to default on their mortgages, because relatives here and abroad often provided help to those in need,” von Hoffman found for one research project in Georgia.

But pooling resources sometimes hurts an individual’s ability to take on more debt, he said. If someone is a part-owner of her siblings’ homes, for example, a conventional lender may not extend another loan for her own home purchase. It can also make it more difficult for an individual to sell property or establish a credit score, von Hoffman said.

Asians Americans are not the only immigrants who lend money to each other via credit rotating systems, or lending circles. People also use them to build credit histories so they can access traditional lenders — and they often start in immigrants’ home countries.

“If we expats trace lending circles, we must go back to our home countries,” according to an article in XpatNation. “This is where they began, specifically in rural areas or cities under the process of urbanization.”

In the Asian community, there’s an additional wrinkle: Some Asians are averse to debt because it carries negative connotations in their home countries, Kui said. They are used to paying cash, or having to put 30 to 40 percent down on a home purchase.

In fact, the Zillow Group Consumer Housing Trends Report 2017 shows that 52 percent of Asians (compared to 45 percent of all buyers) put 20 percent or more down when they purchase a home.

If they put down that much in the United States, the amount they borrow can become so low that lenders will not offer them the best interest rates. Like other activists who follow minority homeownership, Kui wants lenders to pay closer attention to the economic opportunity they’re missing among high- and low-income borrrowers.

Educating Asian immigrants about how lending works in this country can help — but loan products that cater to their needs would make the whole system work better. “[Lenders] need to develop programs for them,” Kui said. “There is a vast market of eligible buyers of homes among the Asian-American community.