Expanding Access to Credit Could Shrink the Homeownership Race Gap

There is a direct correlation between credit security -- a strong credit history and structural access to credit offerings -- and higher homeownership.

There is a direct correlation between credit security -- a strong credit history and structural access to credit offerings -- and higher homeownership.

The homeownership rate is lower in counties that are more “credit insecure,” home to high numbers of residents with poor or no credit history, cutting off millions — particularly Black and Latinx residents — from the wealth-building advantages of homeownership. The relationship underscores the urgency of efforts to reform the nation’s credit scoring system and make credit more accessible.

Using data from the credit insecurity index published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York combined with homeownership data from the American Community Survey, Zillow found that for every 10-point increase in a given county’s insecurity index score, homeownership fell by 2%. And not only are there fewer homeowners in insecure counties, the value of their homes are typically lower than home values in credit-assured counties.

About 26 million Americans are considered “credit invisible,” with no credit history — roughly one in ten U.S. adults who will struggle to access credit simply because they’ve never accessed it before. And a disproportionately high share of these 26 million Americans are Black or Latinx. Credit invisibles and those with poor credit scores tend to be concentrated in areas deemed credit insecure, where the structural availability of formal credit is lacking. Roughly 12.5 million U.S. adults live in counties deemed credit insecure.

Homeownership is one of the fastest and more reliable ways to grow wealth, especially for communities of color. But achieving it is also incredibly credit-dependent: nearly three-quarters of all home buyers (72%) obtain a loan to help pay for their home, a rate that is even higher for Black (78%) and Latinx (77%) home buyers, according to the 2020 Zillow Consumer Housing Trends Report. Those with good or great credit histories can access cheaper financing, while those with marginal, poor or non-existent credit are left to pay more for the same services — or left behind altogether. Solutions to the problem will rely on a range of reforms including to the decades-old credit scoring system itself, and potentially in expanding access to credit through reforms that will reduce the likelihood of financial institutions denying worthy applicants based on their credit history.

The Biden administration has promised to work on restructuring the current credit system to be more equitable, proposing to replace the current system over the course of seven years through the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The new credit reporting system would take payments not currently included in credit scores — like rental history and utility bill payments — into account going forward, bringing many credit invisibles into the formal sector and lifting up many subprime credit scores.

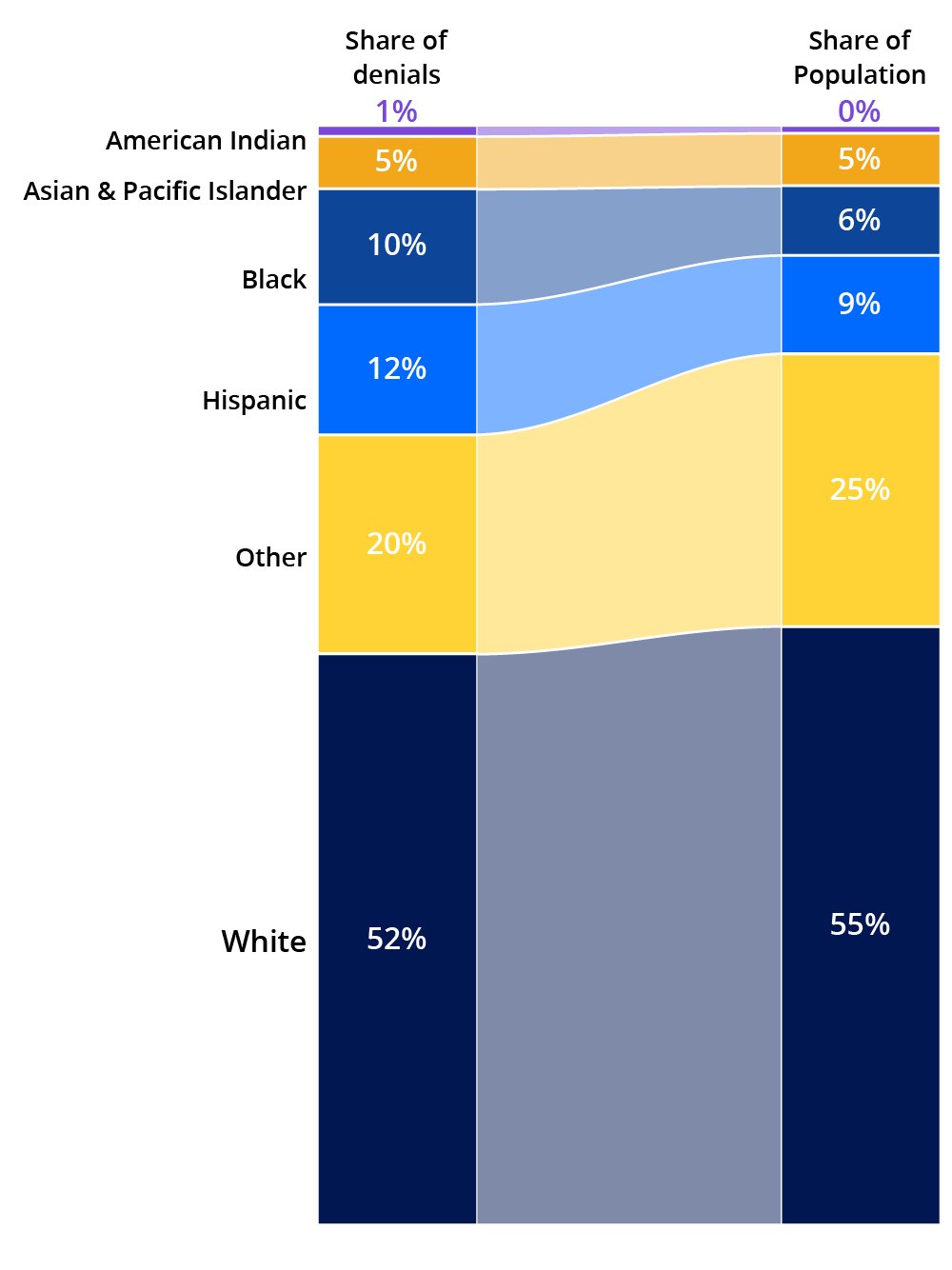

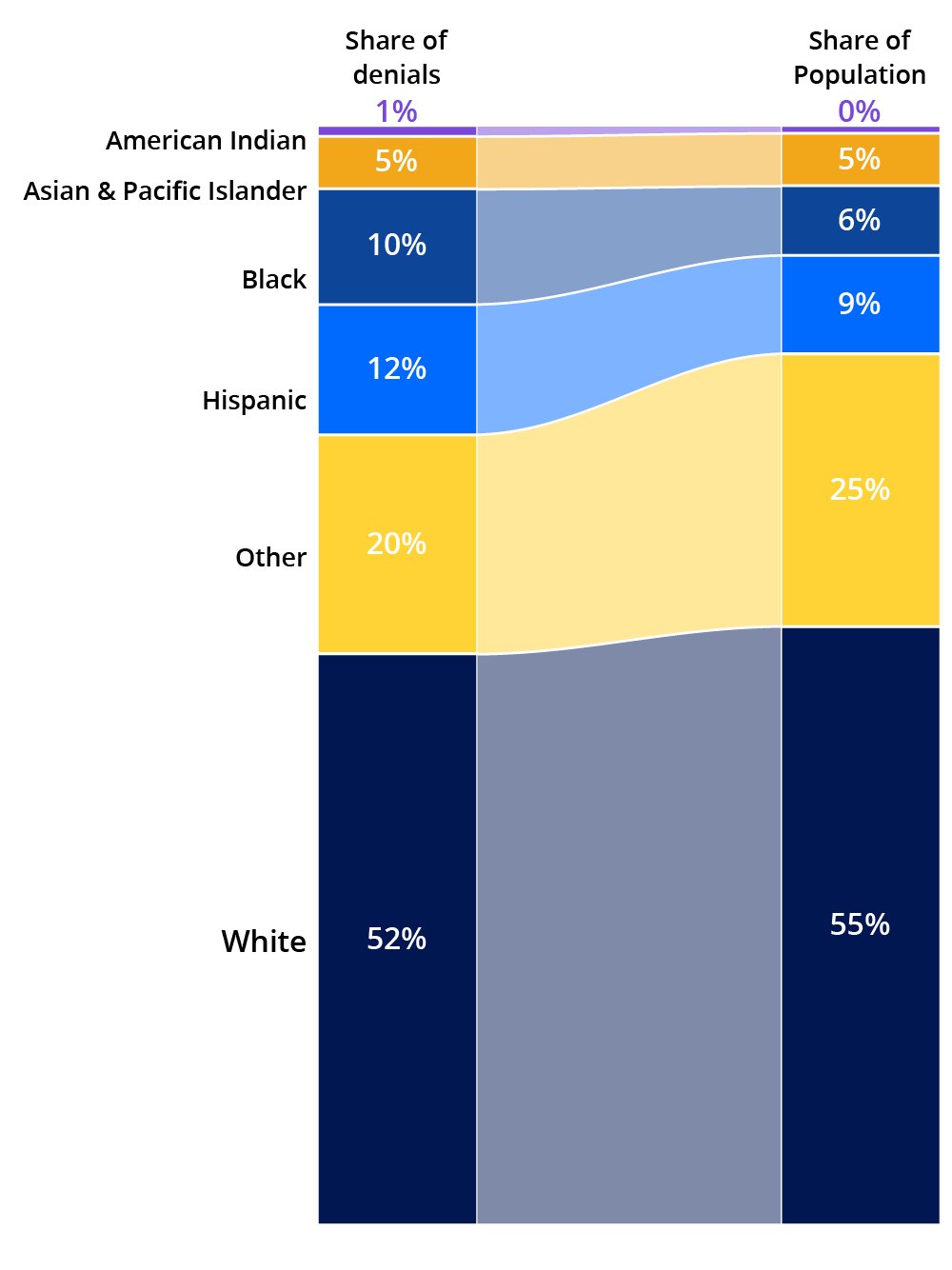

Additional efforts would include expanding the Community Reinvestment Act to provide more, equitable financial services to underserved communities, reducing barriers to credit market entry by eliminating the costly start up steps required for the current credit system and by expanding access to financial services. Currently, credit history (or lack thereof) is the number one reason home mortgage applications are denied to Black applicants, so changes to the system could significantly open up homeownership to groups that have historically been kept away from it.

Getting more people — especially Black and Latinx residents — into the formal credit market and making them explicitly credit visible is critical for a number of reasons. Being credit invisible and shut off from the market can create a perpetual cycle, because oftentimes opening new lines of credit is conditional on having an existing credit score. And credit invisibility is also likely to bleed into future generations, as lack of access to credit now will limit future wealth accumulation and the amount of generational wealth available to pass on, contributing to the racial wealth gap.

But currently, not only are Black and Latinx individuals more prone to being credit invisible, they are also more highly concentrated in counties with higher overall credit insecurity. Almost one-in-10 (9.7%) Black households and 7.9% of Latinx households nationwide live in counties considered credit insecure, compared to 2.7% of white households. Conversely, white households are more than twice as likely (34.7%) than Black and Latinx households (16.3% and 16.2%, respectively) to live in counties considered credit assured.

Credit insecurity is not a standalone issue facing underserved communities, and income and home values are intertwined in the credit universe. When observing the relationship between counties with higher insecurity levels and lower home values, median household income is the missing link — a confounding variable in the relationship that is statistically related to both credit insecurity and home values. As a result, in counties with lower household income, we typically see a higher degree of credit insecurity (negative correlation) and lower home values. While it looks like credit insecurity is predictive of lower home values, it is actually household income that simultaneously predicts both. Areas with low levels of income growth are more likely to stay that way if there is limited access to credit, which in turn leaves home values low.

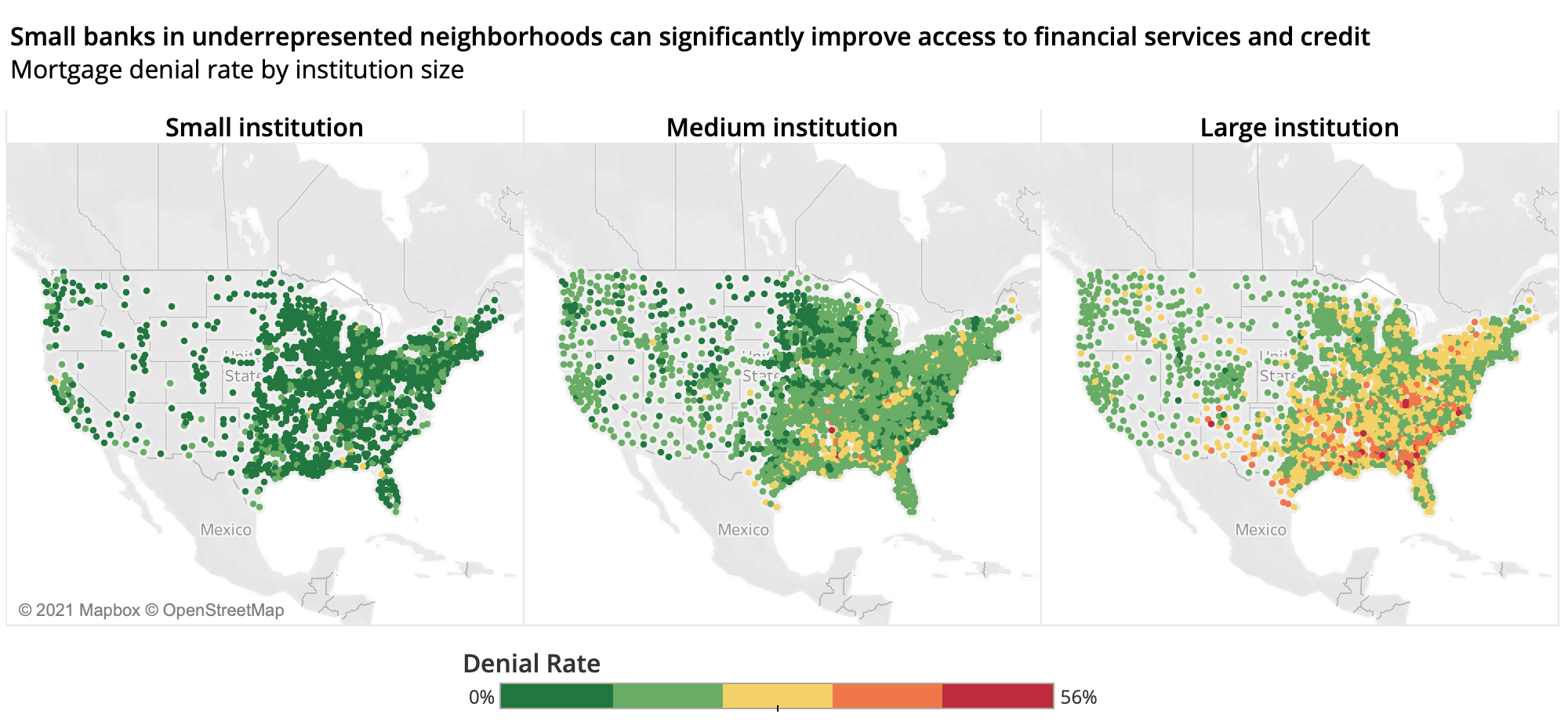

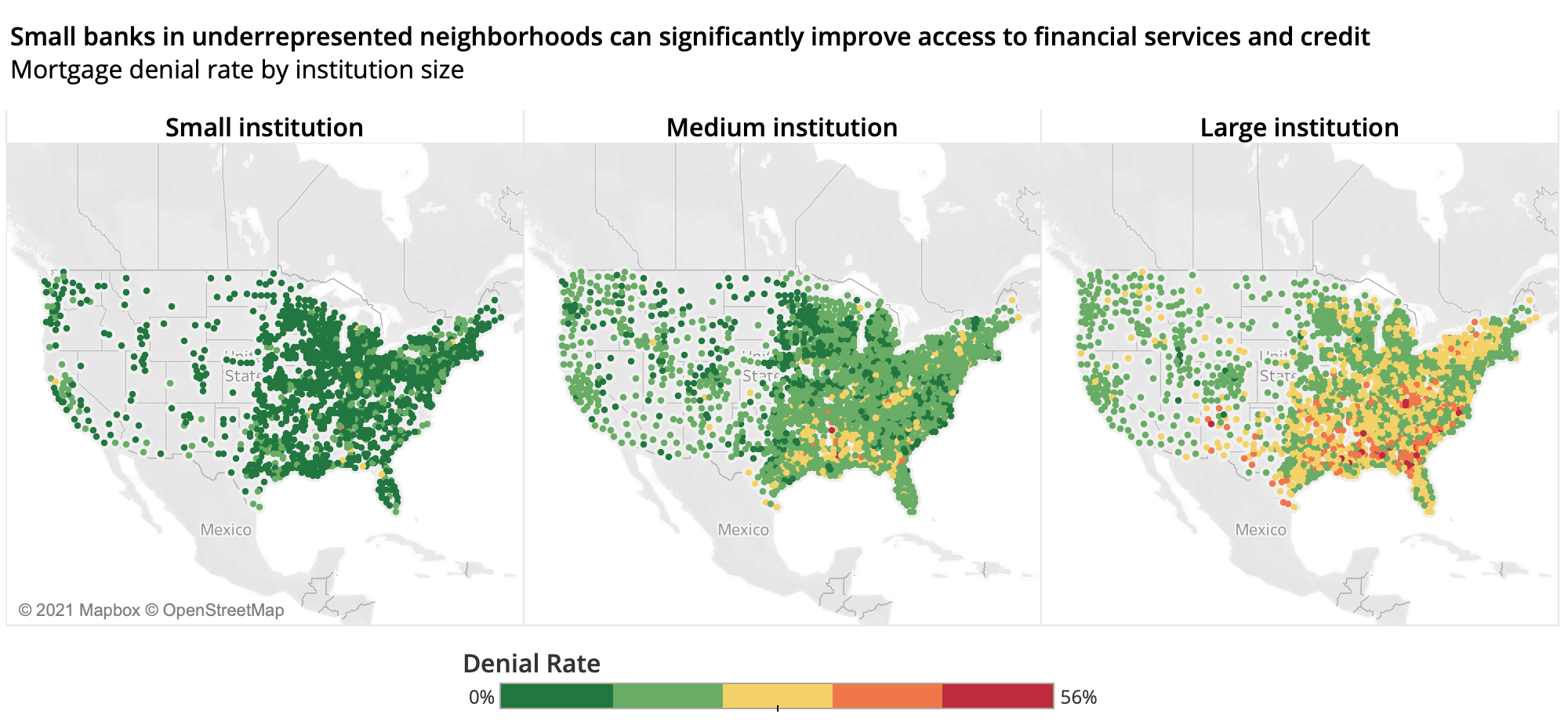

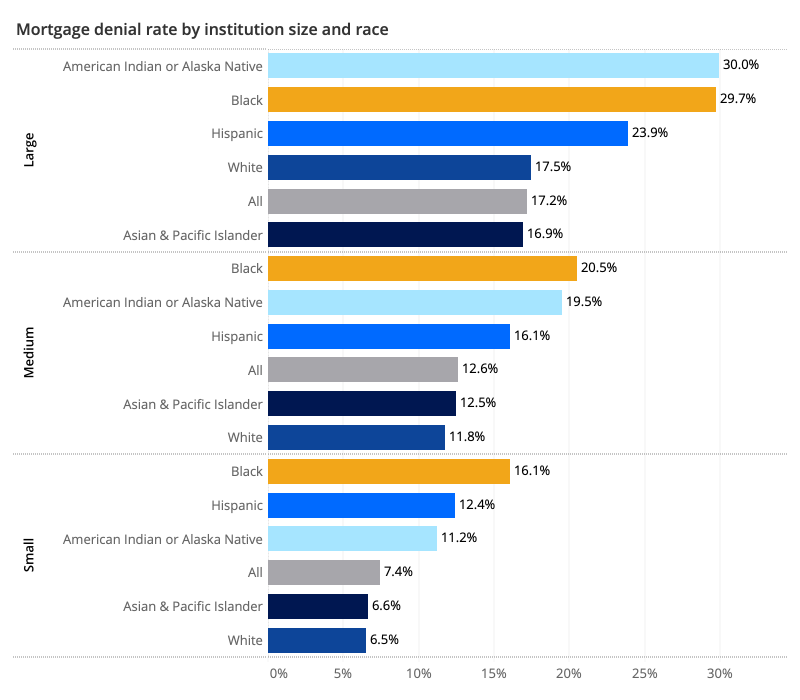

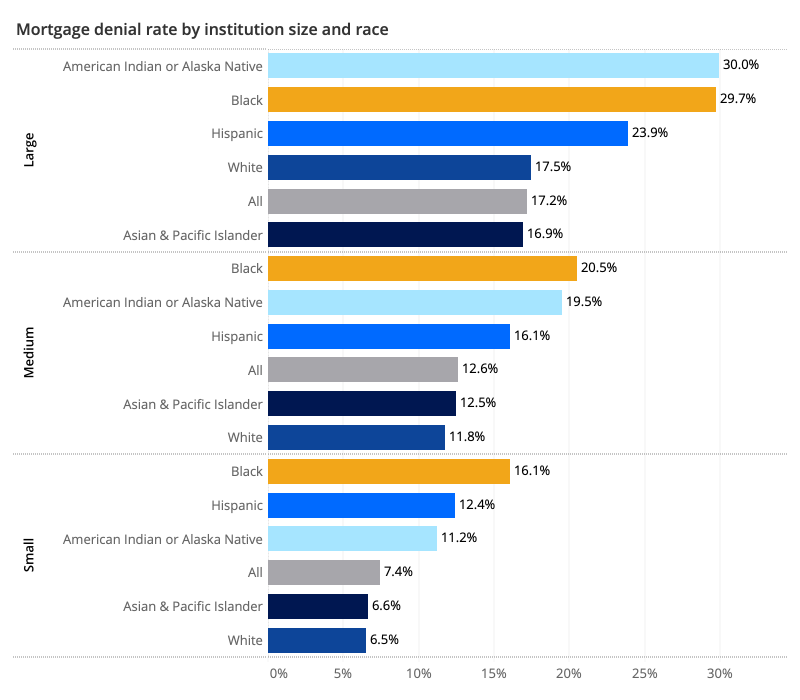

Of course, access to credit, access to financial services and homeownership in general also go hand-in-hand. Black and Latinx adults in the U.S. are far more likely to be unbanked (no bank accounts) or underbanked (relying on informal, often predatory financial services) than white adults. But the simple presence of small banks in underrepresented neighborhoods can significantly improve access to financial services and credit, providing a lifeline to those often left behind by much of the broader financial sector. The overall mortgage denial rate at small banks — those with less than 1000 applications received — was 7.4% in 2019, less than half the rate (17.2%) at large banks, according to an analysis of 2019 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data.

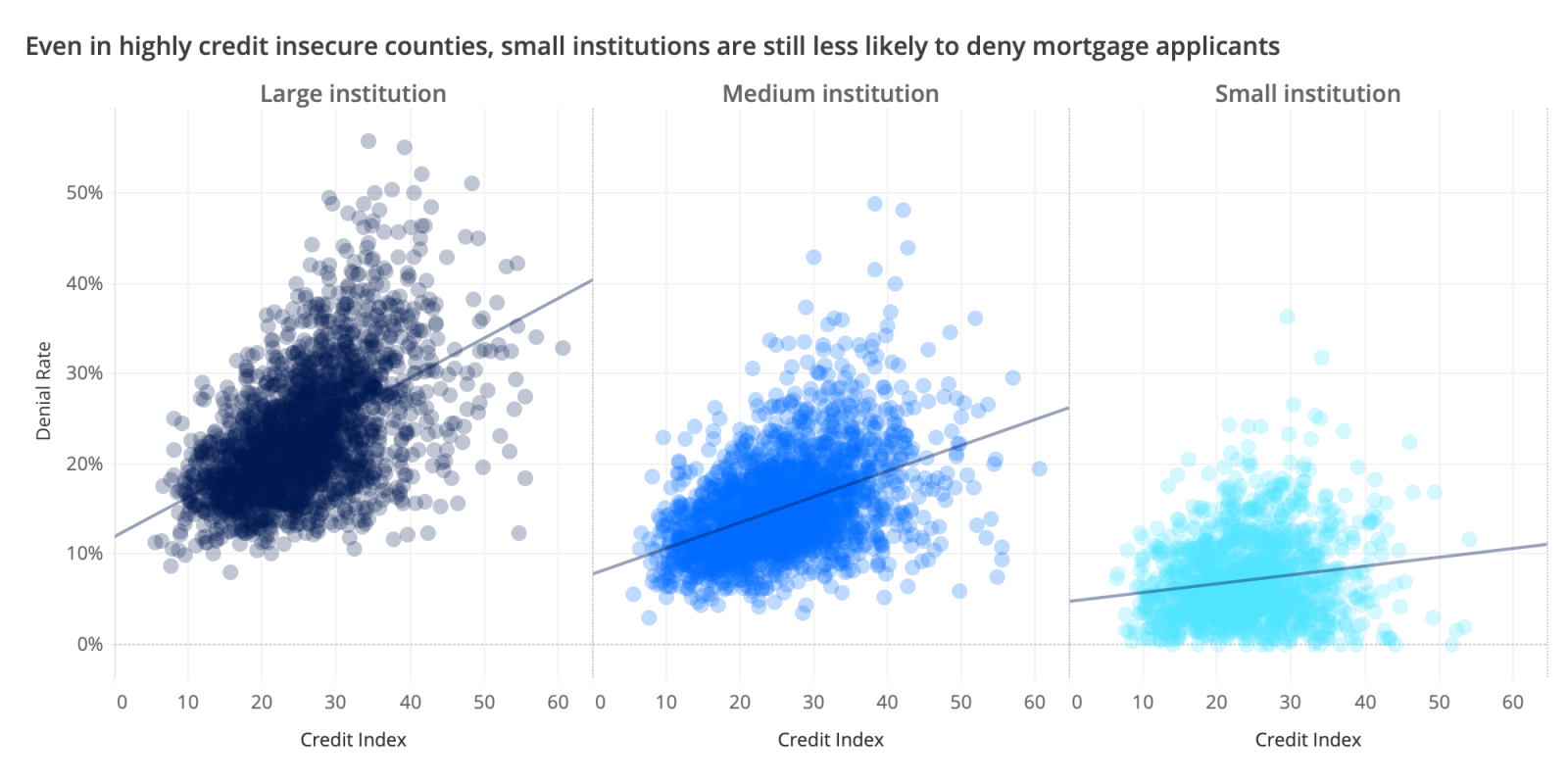

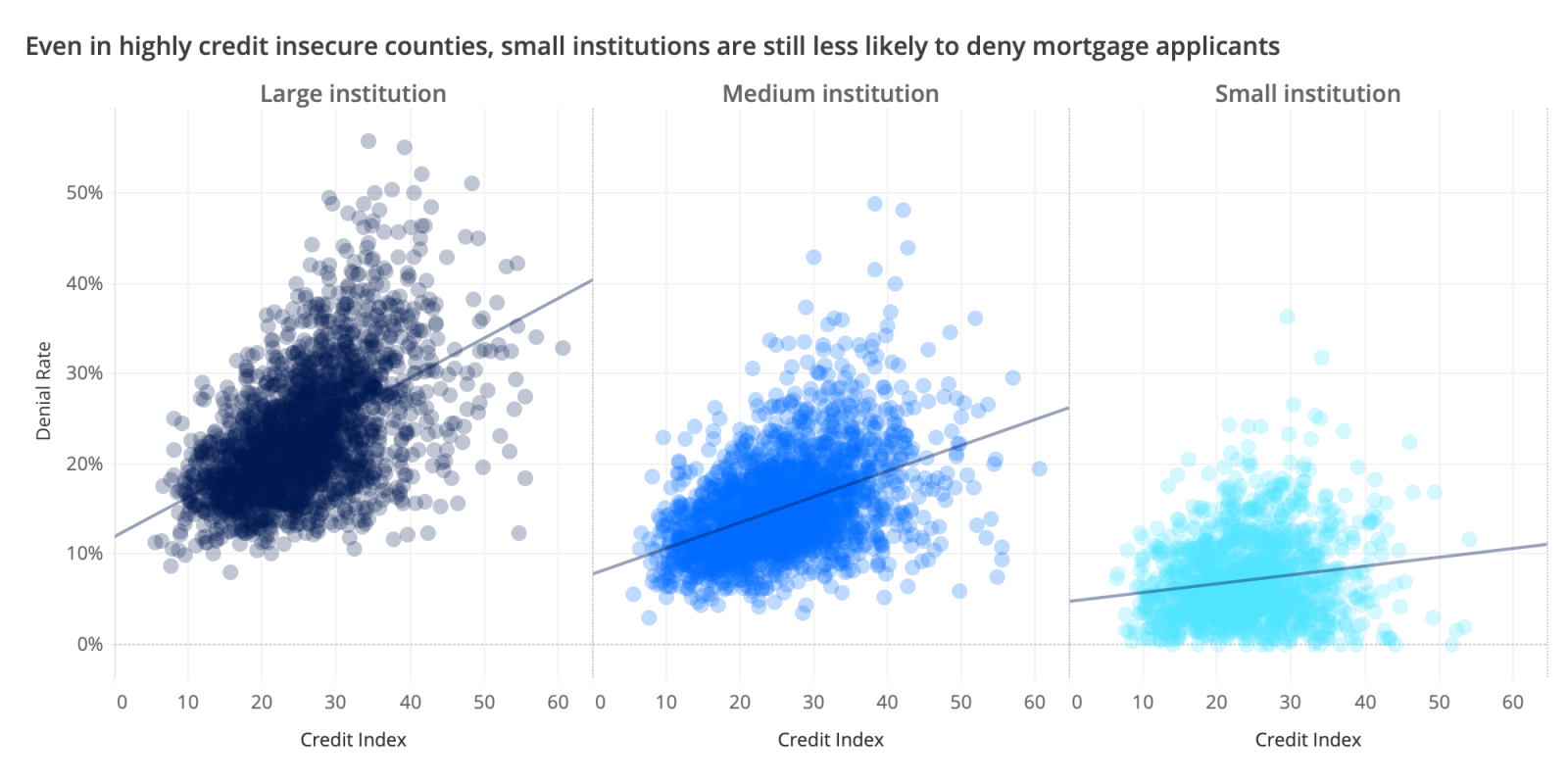

Small banks were also significantly less likely to deny a loan based on credit history than large banks. For small banks, only 2.6% of all mortgage applications were denied based on credit, again less than half the rate (5.7%) at large banks. Combining this data with the credit index from the New York Fed gives us a glimpse of how these smaller institutions can be key to providing equitable credit opportunities even in counties considered credit insecure. Nationwide, small banks have much lower mortgage denial rates in relation to the county’s credit index than medium and large banks. In other words, even in counties with high rates of subprime credit scores, credit invisible people and individuals with poor credit history, small institutions are still less likely to deny mortgage applications than large banks.

It also does not appear to be the case that these small banks are charging more for this credit — we observed similar interest rates and generally lower fees for small banks compared to large ones. However, there is one notable place where small banks rank just as poorly if not worse than their larger counterparts. Black mortgage applicants are denied by small lenders at 2.5 times the rate of white applicants. Large lenders were 1.7 times more likely to deny Black applicants than their white counterparts. So even while the denial rate overall is lower for small institutions, racial inequality still exists. There is more work to be done.

Increasing access to financial services is one of the best ways to promote a healthy relationship with credit in a community, but unfortunately in the United States, financial services are in short supply in many non-white neighborhoods. Policies that regulate institutions to ensure there is equitable access to financial services and prioritize underserved areas, including the Community Reinvestment Act, will help promote more equitable lending across institutions and help to bridge the gap in homeownership.

But while supporting small banks can help bridge the credit gap in many communities, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure credit access for BIPOC and other communities is equitable. Our findings show that more equitable credit could potentially increase homeownership rates and demand for housing in BIPOC communities, and higher home values are a likely consequence.

Zillow used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2007, 2012, and 2018 American Community Surveys combined with data from the New York Fed’s report on Unequal Access to Credit (data for years 2007, 2012, and 2018) to estimate the relationship between a county’s credit security index and homeownership rates. The data was then combined with Zillow’s data on home values (via the Zillow Home Value Index) to estimate the relationship with a county’s credit security index and home values over time.

Zillow also utilized 2019 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data (most recent year available) to estimate the relationships between the above and mortgage denials, specifically broken out by the size of lending institutions. The categorization of institution size is based on the number of mortgage loan applications each institution received in 2019, with ‘small’ lenders classified by receiving less than 1,000 loan applications, ‘medium’ receiving 1,000 to 100,000 loan applications, and ‘large’ receiving over 100,000 loan applications across all branches in 2019.