As Fair Housing Month begins, it’s important to look back at the landmark legislation that helped bring us to this point. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 reversed decades of overtly (and more subtle) discriminatory housing practices, and established a number of critical protections still important today.

As Fair Housing Month begins, it’s important to look back at the landmark legislation that helped bring us to this point. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 reversed decades of overtly (and more subtle) discriminatory housing practices, and established a number of critical protections still important today.

Here’s an overview of the Act, what it does and how its enforced, challenges to it today and over time, and what its continued evolution may look like going forward.

What is the Fair Housing Act?

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law in 1968, following a prolonged legislative battle and on the heels of the tragic assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The Act extended the basic discrimination protections within the 1964 Civil Rights Act into the housing market. It explicitly prohibits discrimination in housing on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex – and, following amendments in 1988 – familial status and disability. The Act also protects specific types of real estate activity from discrimination, primarily aspects of the sale, rental and financing of dwellings.

Today, the Fair Housing Act serves as foundational legal protection from discrimination in housing. But despite its judicial successes, it remains subject to significant debate, often regarding lingering residential segregation, the application of disparate impacts and the mandate to affirmatively further fair housing. More on those later.

What led to the Fair Housing Act?

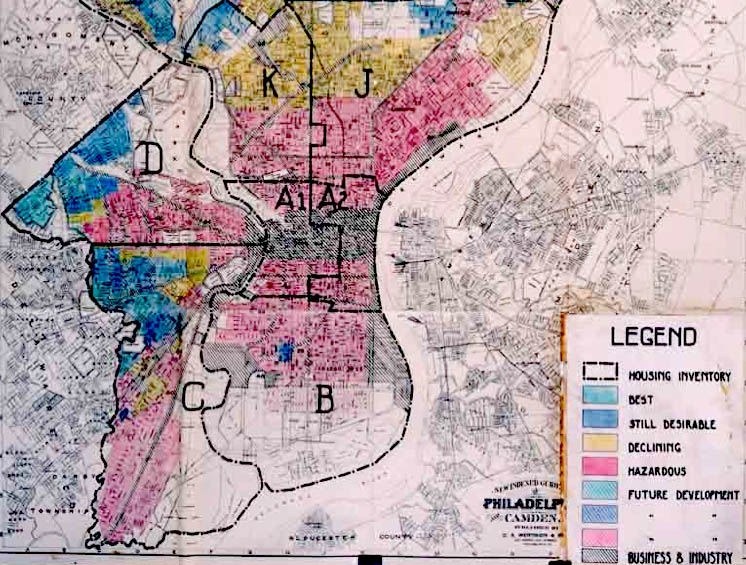

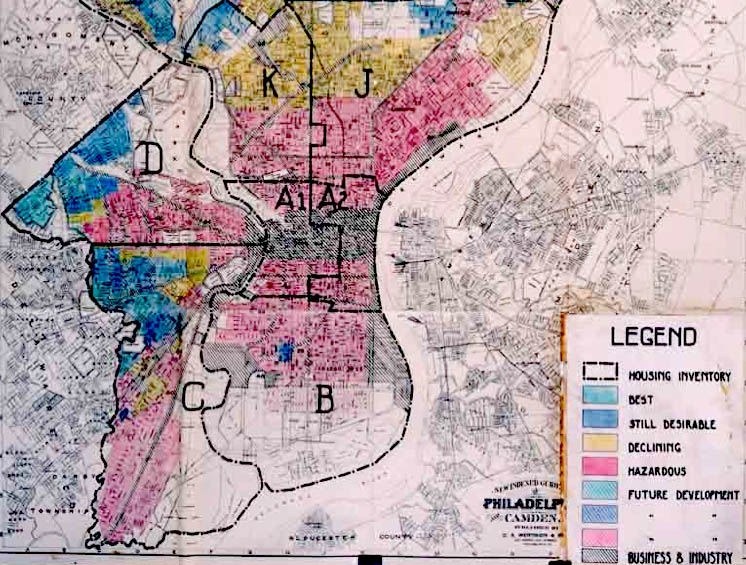

A 1936 map of Philadelphia showing redlining of lower-income neighborhoods. Households and businesses in the red zones could not get mortgages or business loans.

Residential segregation, repeatedly molded and maintained through fear and violence, was perpetuated by long-standing discriminatory housing policy. Institutionalized, racist practices within government and private organizations, together with discriminatory actions by individuals in the real estate world, coalesced into a landscape of systemic disadvantages for minorities, particularly black homebuyers and renters.

What sometimes began as discriminatory actions by individual communities or agencies became government policy. The Federal Housing Administration institutionalized the practice of redlining – refusing to issue loans on properties located in black communities (literally, marked by red ink). Redlining encouraged a mass exodus of white homeowners from some neighborhoods (even some with few black residents) deemed “hazardous,” thus causing property values in those areas to fall. The Federal Housing Administration also encouraged restrictive covenants, clauses in deeds or leases prohibiting the occupation of property by particular groups, often blacks. Additional government policies, including the inability of black veterans to purchase homes using the GI bill, further exasperated these inequities.

Through these forces and more, America’s racial residential patterns became starkly divided. The Kerner Commission report of 1968 described the situation as, “the division of our country into two societies; one, largely Negro and poor, located in the central cities; the other, predominantly white and affluent, located in the suburbs and in outlying areas.”

How did the Fair Housing Act pass?

The Fair Housing Act was a tough sell for President Johnson. Previous attempts to pass the bill beginning in 1966 were met with stiff opposition from both parties. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the resulting unrest in major cities were big catalysts for the eventual passage of the Fair Housing Act. According to The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), “President Johnson viewed the Act as a fitting memorial to the man’s life work, and wished to have the Act passed prior to Dr. King’s funeral in Atlanta.”

Another significant driver for fair housing during this particular period was the return of black and Hispanic veterans from the Vietnam War. Carlos Campbell, a decorated Naval Officer appointed to a job in the Pentagon, was unable to rent a home in white neighborhoods near his new post. He joined forces with the Act’s sponsors, Senators Walter Mondale of Minnesota and Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, to push the bill forward.

Around the same time, the influential and scathing Kerner Commission report was published. In this context, President Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act on April 11, 1968, one week after the assassination of Dr. King. The Act was later amended several times to include additional protections.

How does the Fair Housing Act work?

The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity within HUD enforces laws and creates polices to ensure equal access to housing under the Fair Housing Act. Individuals who feel they have been discriminated against in a manner prohibited by the Act can file a complaint with HUD.

The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity within HUD enforces laws and creates polices to ensure equal access to housing under the Fair Housing Act. Individuals who feel they have been discriminated against in a manner prohibited by the Act can file a complaint with HUD.

Once a complaint is filed, HUD contacts the alleged violator regarding the complaint, requesting a response. HUD then works toward an agreement between the parties, and if an acceptable agreement is reached, HUD will take no action. If a conciliation agreement is broken, however, HUD recommends the Department of Justice take action.

After investigating a complaint, if HUD determines discrimination probably occurred, the case could be heard in an administrative hearing or Federal District Court. If a judge rules that discrimination did occur, the violator may be ordered to compensate the plaintiff for damages, make housing available, pay a civil penalty and/or pay reasonable attorney’s fees. One may also file a suit at their own expense in Federal or State Court, depending on the actions already taken.

In addition to relying on complaints, in 1991 the Department of Justice established the Fair Housing Testing Program. Posing as prospective renters or buyers, testers are sent to properties to determine whether housing providers comply with the Fair Housing Act. According to the Department of Justice, “The vast majority of testing cases filed to date are based on testing evidence that involved allegations of agents misrepresenting the availability of rental units or offering different terms and conditions based on race, and/or national origin, and/or familial status.” Housing advocates and nonprofit organizations are also a vital source of housing discrimination testers, and assist the federal government in enforcing fair housing laws.

What’s changed since the Fair Housing Act passed?

Since the Fair Housing Act’s passage, countless individuals have successfully enforced their rights to fair housing. With equal treatment in housing as the law of the land, all individuals and families have a tried-and-true avenue to help ensure protection of their rights.

A major victory for fair housing occurred after passage of the 1988 Fair Housing Amendments Act, which (among other things) extended protections to individuals with disabilities. An important outcome of that legislation was the ability to challenge local zoning laws prohibiting community or group living for individuals with disabilities.

Still, significant challenges to housing equality persist. On one hand, recent lawsuits brought by the federal government demonstrate that the Act remains an important tool for fighting discrimination. On the other, these lawsuits show discrimination in housing remains a serious problem, and the threat of litigation hasn’t deterred all nefarious behavior.

Equally difficult to grapple with is the persistence of racial residential segregation even almost 50 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act. Some criticize insufficient enforcement of the Act for an inability to eliminate the very patterns of residential segregation it was intended to fix. America’s neighborhoods remain deeply divided by race. And this has serious consequences for health, education, and employment.

How does fair housing look today and in the future?

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy

In 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that disparate impacts were sufficient cause to find violations of the Fair Housing Act. Policies can be deemed illegal today, even without evidence of intentional racial bias, if the effects of the policy are shown to disproportionately harm groups protected by the Fair Housing Act. In writing the decision, Justice Anthony Kennedy advised that identifying statistical disparities in housing were not enough evidence; rather, it should be evident that particular policies caused the disparity in question.

Another way the Fair Housing Act may be leveraged to combat segregation is enforcement of the Act’s clause to affirmatively furthering fair housing. Beyond prohibiting discrimination in housing, the Fair Housing Act requires governments to actively work toward racial integration of neighborhoods. Some critics of the Act insist this provision has not been adequately enforced, while others argue affirmatively furthering fair housing oversteps the intention of the law and the powers of the federal government. In 2015, the Obama administration announced a new rule requiring cities and counties to study and report their housing patterns in order to meet desegregation goals. According to the Washington Post, “officials insist that they want to work with and not punish communities where segregation exists. But the new reports will make it harder to conceal when communities consistently flout the law. And in the most flagrant cases, HUD holds out the possibility of withholding a portion of the billions of dollars of federal funding it hands out each year.”

In addition to the protections guaranteed by the Fair Housing Act, many local governments extend housing protections further. For example, while not protected in the Act, many cities, states and counties forbid housing discrimination based on sexual orientation or source of income (often Housing Choice Vouchers or other government benefits). Also, while some evidence points to anti-density zoning or rising housing costs as significant contributors to segregation, many communities are fighting back by prioritizing affordable housing, dense development and inclusionary zoning policies.

Related: