The majority of Latino Americans aspire to homeownership. Community activists say so, and surveys bear them out: 70 percent of Hispanic respondents to the Zillow Housing Aspirations Report say owning their own home is necessary to live the American Dream.

Lautaro Diaz, vice president for housing and community development at the nonprofit UnidosUS (formerly the National Council of La Raza/NCLR) in Washington, D.C., has seen how homeownership can pull people toward that dream: UnidosUS and one of its 300 member organizations sold a home in the D.C. neighborhood of Anacostia to a lower-income family. A mother with three children, her mother, and another family member, who had been living in three different homes, came together in a home that cost them $170,000.

The home they bought has “completely changed the direction the family was thinking they were going to have to go,” Diaz said. “Their family balance sheet now has wealth.” It means stability — financial and otherwise.

The stability of home

Living in one place can have a huge impact on school-age children, something Diaz learned as a child. Born in Chile, he attended seven schools before he turned 15. “I was relatively lousy in school, because I had to keep re-making my social network,” he said.

Children’s schoolwork improves after their parents buy homes and settle down, Diaz explained. “They have a sense of belonging, a veneer of stability and permanence that increases confidence.”

In many cases, their families’ housing expenses also drop. The Anacostia family’s new home was big enough that they combined households and stopped paying rent on three separate places. “That means they have more money for better food, for educational stuff. They can let the children play sports,” Diaz said.

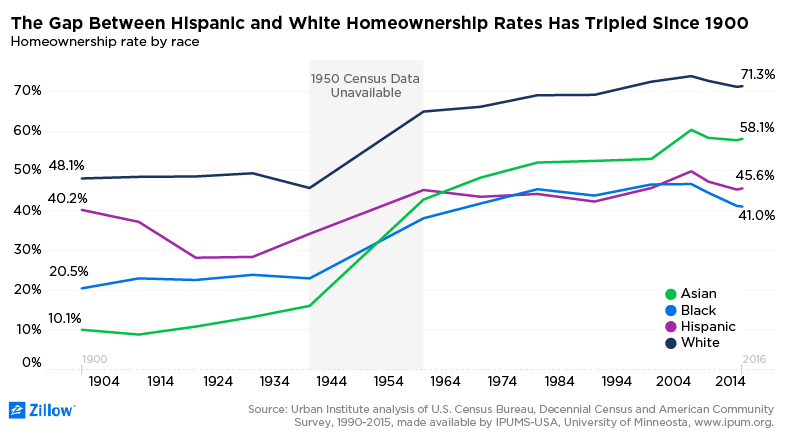

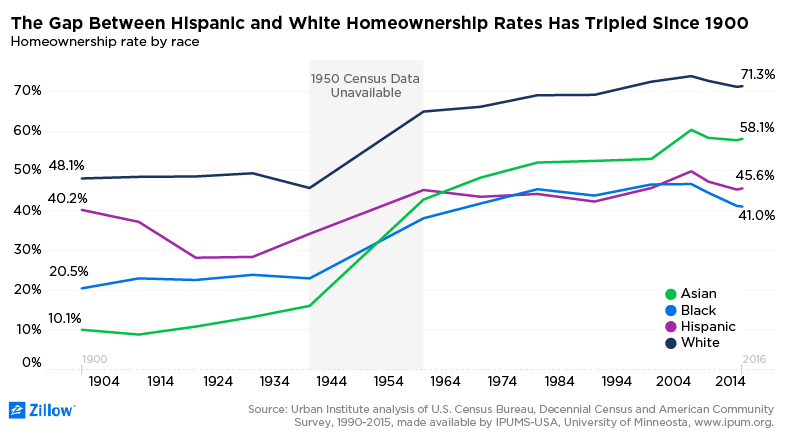

Latinos have been subject to the same racist housing policies that hurt blacks, including redlining and restrictive covenants. But many Latinos came to the United States after those practices became illegal, so they have encountered different hurdles.

Immigrants and housing

Owning a home starts with believing that that is even possible, Diaz said.

“If you have parents who own their home, they’re going to encourage you to do the same as soon as you’re in a position to do that,” he said. If you don’t, you might see a friend buy a home or learn about homeownership in a class — and that gives you hope and can put you on the path.

After people decide to go for the homeownership dream, a major hurdle is income. Latinos make $19,000 a year less than whites, on average, and that makes it harder to save for a down payment.

“They have to channel their resources into buying a home, and not necessarily sending money back to family in Mexico or Latin America,” Diaz said. They also have to build a credit history that appeals to lenders, which means borrowing at least a little before applying for a mortgage. Buying on credit can be a tricky proposition for many immigrants who see debt as a slippery slope to bankruptcy.

Some organizations offer solutions like zero-interest loans that small groups of immigrants lend to one another, for the purpose of building credit. Their monthly payments are reported to credit bureaus, giving them access to mainstream lending so they don’t have to rely on payday loans.

Jose Quinonez is a 2016 MacArthur fellow who runs the Mission Asset Fund in San Francisco. Its lending circles model facilitates lending among small groups of immigrants for the purpose of building credit. The payments are reported to credit bureaus.

The organization started in 2008 with four people in one lending circle. They lent each other $200 a month, for a total of $800. Now, the program is active in 17 states and the District of Columbia, and made more than 6,300 loans in 2015.

Alternative credit scoring is another avenue toward homeownership, said Alejandro Becerra, director of research at the National Association of Hispanic Real Estate Professionals. Some systems now include rent and utility payments, something not counted in traditional credit scores. He also wants more traditional financial services companies to open offices in Latino neighborhoods, where he sees payday lenders and pawn shops now. And they should offer home loans that are suited to those communities, he said.

Good, creative mortgages needed

Some Latinos — newer immigrants in particular — face a challenge regarding how little they want to borrow. Many lenders either don’t offer such small mortgages or charge more for them.

“We’re going to have to be a lot more creative,” Diaz said. He’s not talking about the kind of creativity some lenders demonstrated during the housing bubble, when 47 percent of the loans issued for home purchases by Hispanics were subprime, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Such predatory lending devastated many Latino communities, where home values stayed well below their peak for years.

UnidosUS works with borrowers to help people become pre-qualified, which saves lenders time and makes them more likely to work on low-dollar mortgages.

“I’m trying to challenge this notion that poor people are somewhat broken,” the Mission Asset Fund’s Quinonez told PBS NewsHour. “When I look at my community, I know that people are truly financially savvy, particularly immigrants. They know more about interchange rates than any of us … and they manage budgets in multiple households across countries.”

With all that going for them, building credit becomes a way to prove their worth to the lending system — a step toward homeownership.