Low-Income Housing Tax Credits: Why They Matter, How They Work and How They Could Change

As markets struggle to meet increasing demand and provide sufficient affordable housing, the White House and Congress have made proposals that could lower the value of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits – the main tool Uncle Sam has to help get that kind of housing built.

As markets struggle to meet increasing demand and provide sufficient affordable housing, the White House and Congress have made proposals that could lower the value of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) – the main tool Uncle Sam has to help get that kind of housing built.

Here’s an explanation of how LIHTCs work, and what those proposals might mean for the program going forward.

Why do LIHTCs matter?

For starters, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits are responsible for creating a lot of affordable housing across the country. Between its start in 1987 and 2014, LIHTC projects created 2.8 million housing units across 43,000 developments. In supply-strapped, expensive cities, LIHTC developments can help create rental units priced for folks earning well below the region’s average income.

Second, we’re heavily invested in the program. The federal government spends between $7 billion and $8 billion per year on LIHTCs, making it the largest provider of government-funded affordable housing construction. Between 1987 and 2006, almost one-third of all newly constructed multifamily units used the LIHTC program. The tax credits fuel an entire cottage industry of developers, syndicators, investors, and tax specialists who get projects off the ground.

How do the credits work?

There are two types of LIHTCs: A 4 percent credit (which fluctuates and isn’t always worth exactly 4 percent) and a 9 percent credit. [1] The 4 percent credits are much shallower, are often paired with government-backed loans and do not require a competitive application. The 9 percent credits are significantly more valuable, are limited by the government and require an application process. “9 percent” and “4 percent” refer to fractions used in the formula to determine the exact value of each credit – more on that later.

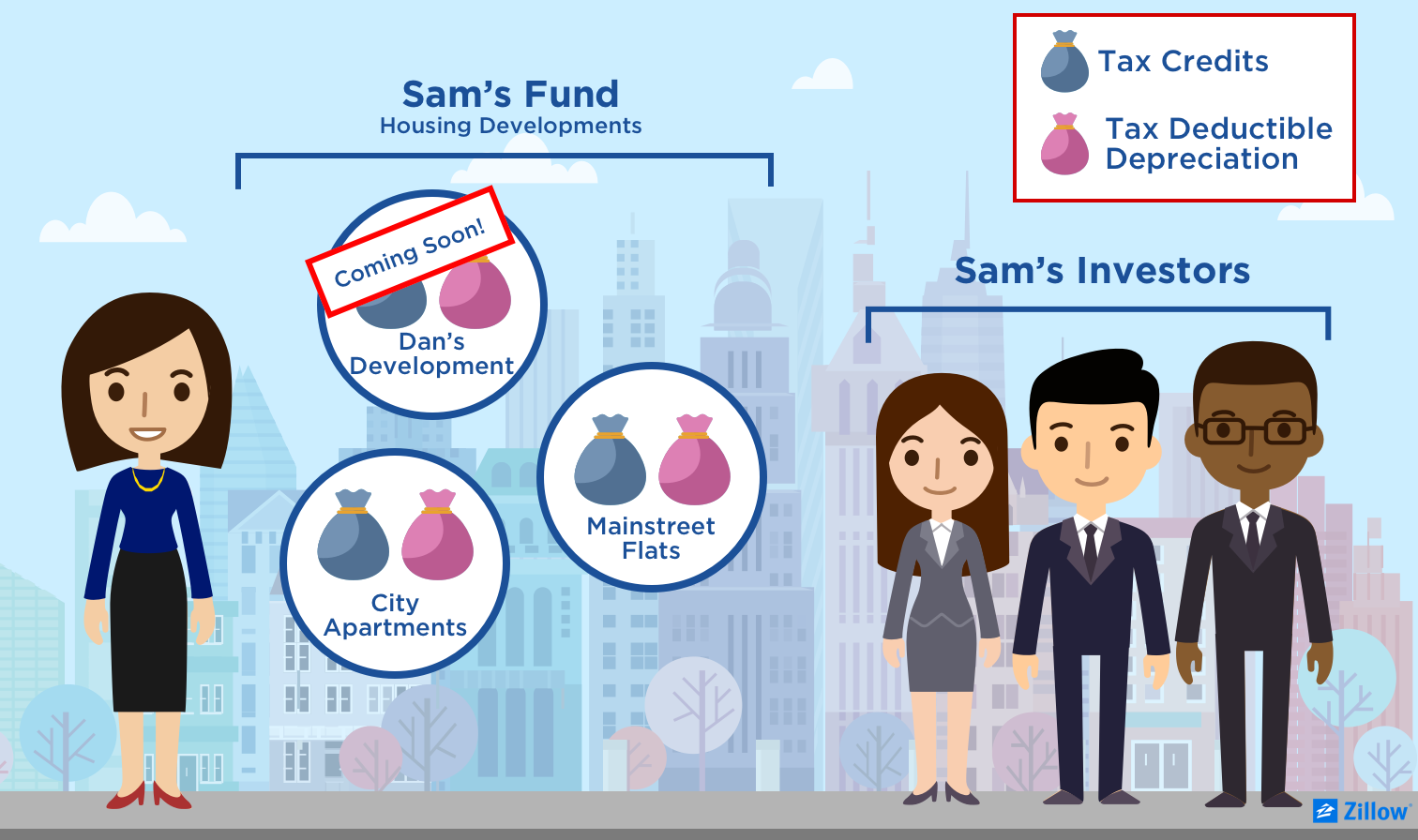

There are also two types of legal structures used for LIHTC projects: direct partnerships and multi-investor funds (the latter is more common). LIHTC housing starts with a project developer, often a nonprofit or for-profit company specializing in affordable housing developments.

Let’s walk through how a hypothetical 9 percent credit project with multiple investors would work:

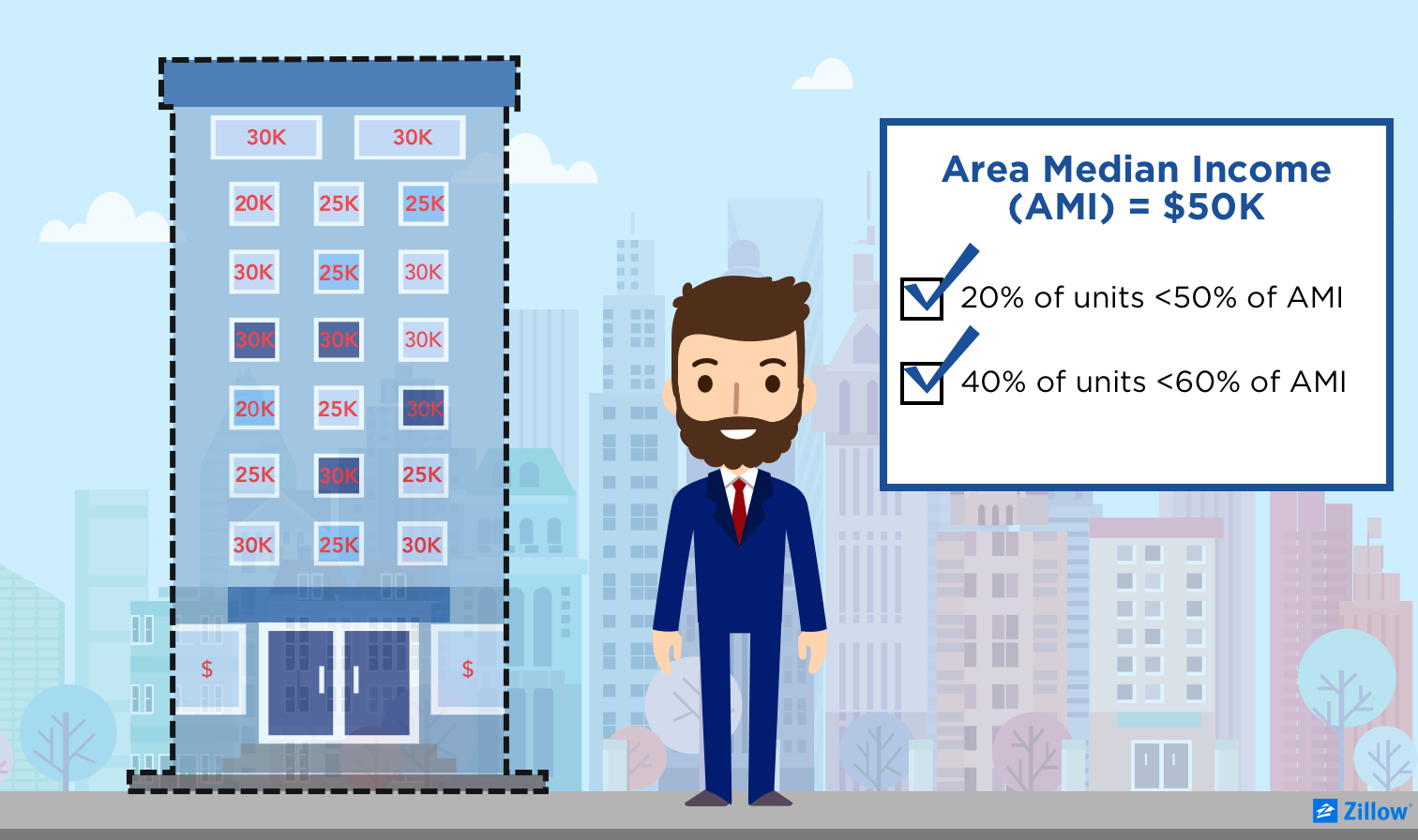

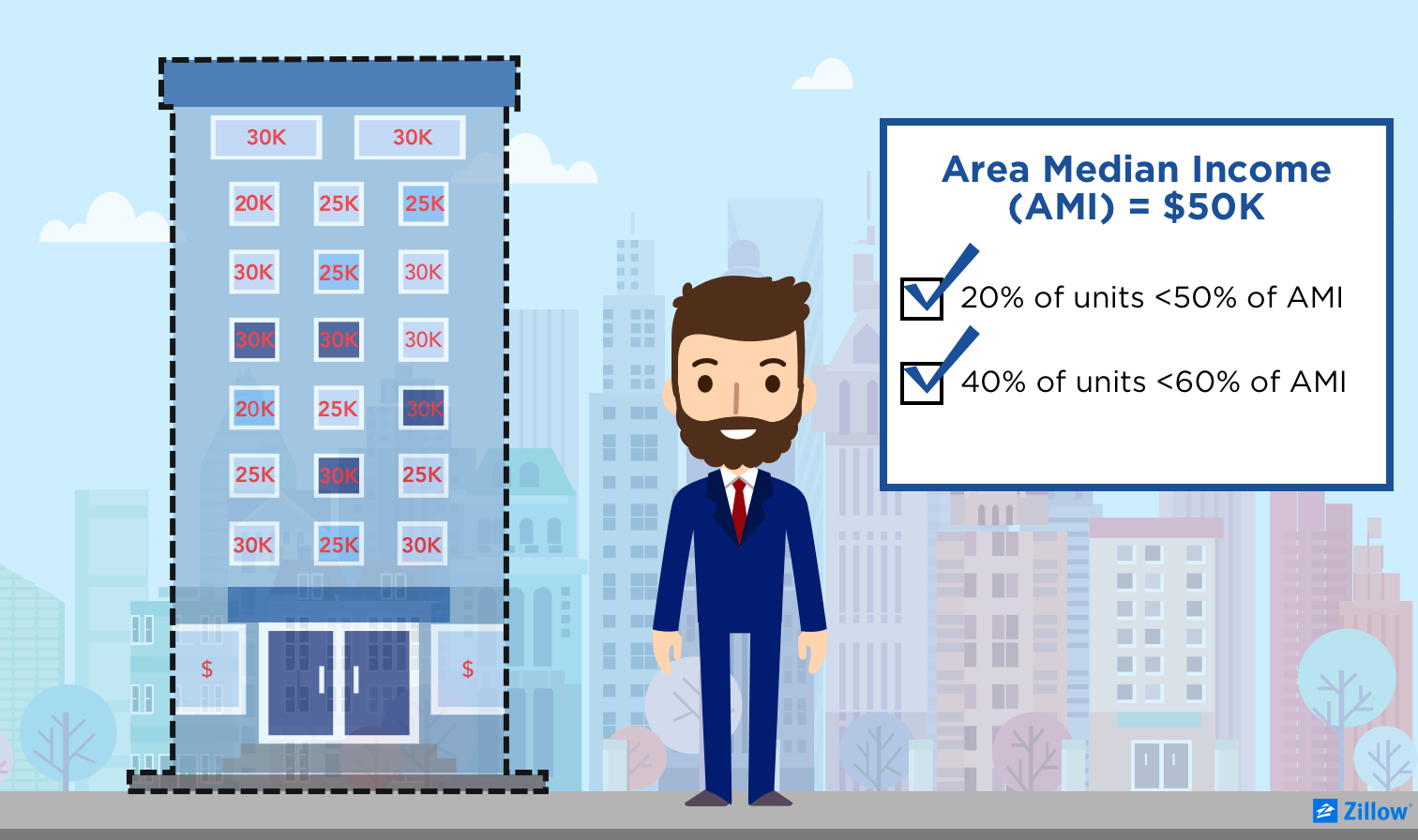

- Developer Dan plans to construct 100 affordable units. To qualify for LIHTCs, Dan must reserve at least 40 of these units for renters earning less than 60 percent of the area median income (AMI), or 20 of his units for renters earning 50 percent of the AMI. Like most developers competing for scarce tax credits, Dan plans to exceed both minimum criteria and offers all 100 units to low-income renters. Unlike other housing assistance programs, rents in LIHTC properties are not tied to tenants’ income, but rather capped at 30 percent of the income limits for each unit. Because of this, some of Dan’s eventual tenants may earn even less than 50 percent of the AMI. They can either pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent or, like many LIHTC tenants, acquire an additional subsidy to bridge that gap.

- In order to charge cheaper rents capped at this fixed price, Dan applies to his state’s Housing Credit Agency (HCA) to receive LIHTC funds. The federal government awards state HCAs a fixed amount of 9 percent LIHTC funds each year, based on the state’s population. HCAs review proposals and award credits based on a variety of criteria, including: number of affordable units; income range of tenants; location; project readiness; and the project’s proposed horizon for remaining affordable.

- LIHTCs are worth a proportion of each project’s “eligible base,” which is the cost of building a low-income housing development excluding certain expenses. If the project is built in certain high-poverty or high-cost areas, LIHTC rules increase the eligible base in order to raise the value of credits. Overall, Dan’s building costs $13 million to build. But some costs – including professional fees, acquiring the land and constructing a retail shop on the first floor – are excluded, leaving him with an eligible base of $10 million. The percent of the eligible base used to construct the units rented to low-income tenants is called the “qualified base.” For example, if three-quarters of the units were built to house qualified low-income tenants, the credits would be based off a $7.5 million qualified base. Because all of Dan’s units are deemed affordable, his qualified base is the same as his eligible base – $10 million.

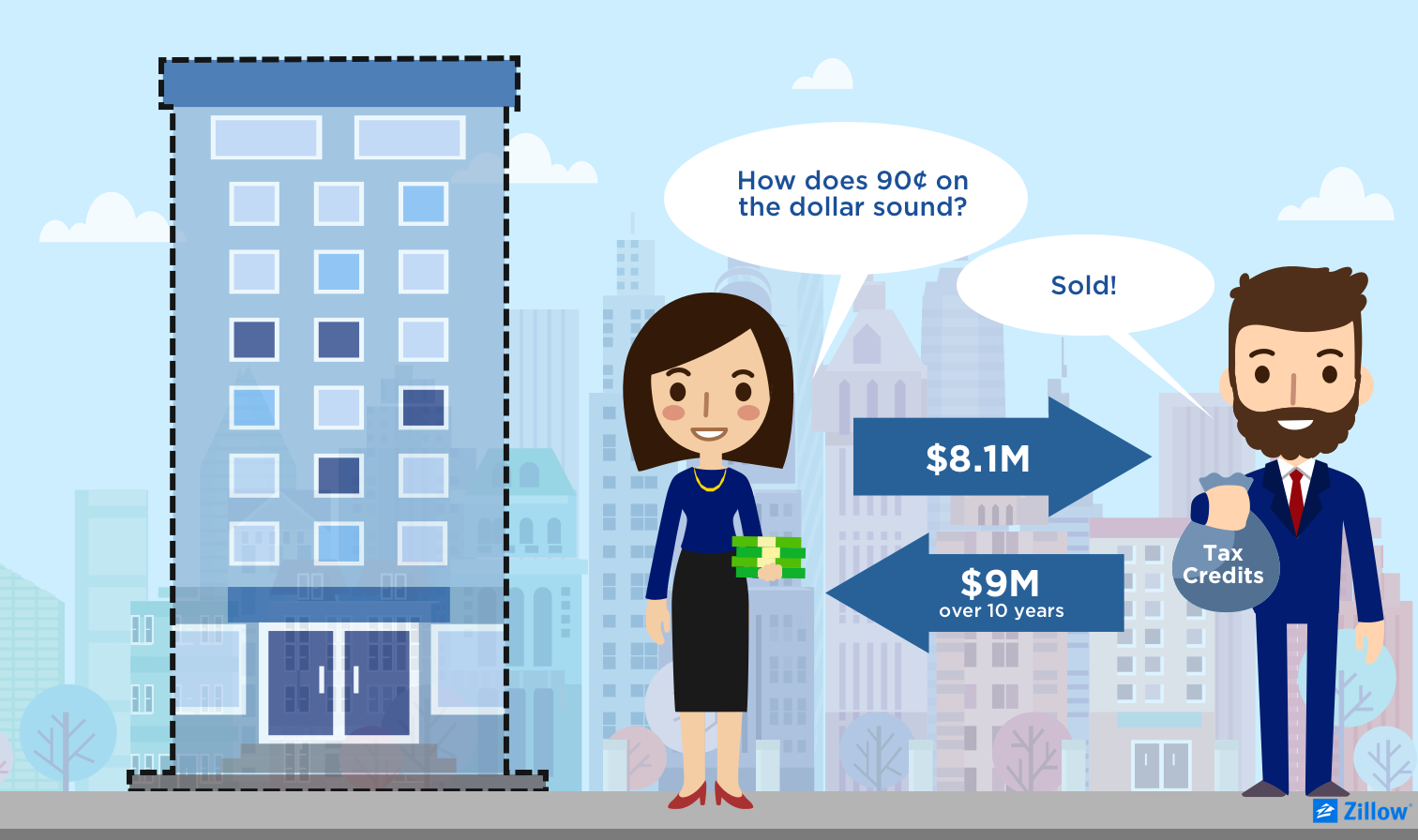

- Because he is using the 9 percent credit, Dan takes 9 percent (as the name suggests) of his $10 million qualified base and arrives at a tax credit value of $900,000 per year. Each year over the next 10 years, the purchaser of these LIHTCs can deduct $900,000 from their taxes. Dan now has a total of $9 million in tax breaks he can sell to fund his development.

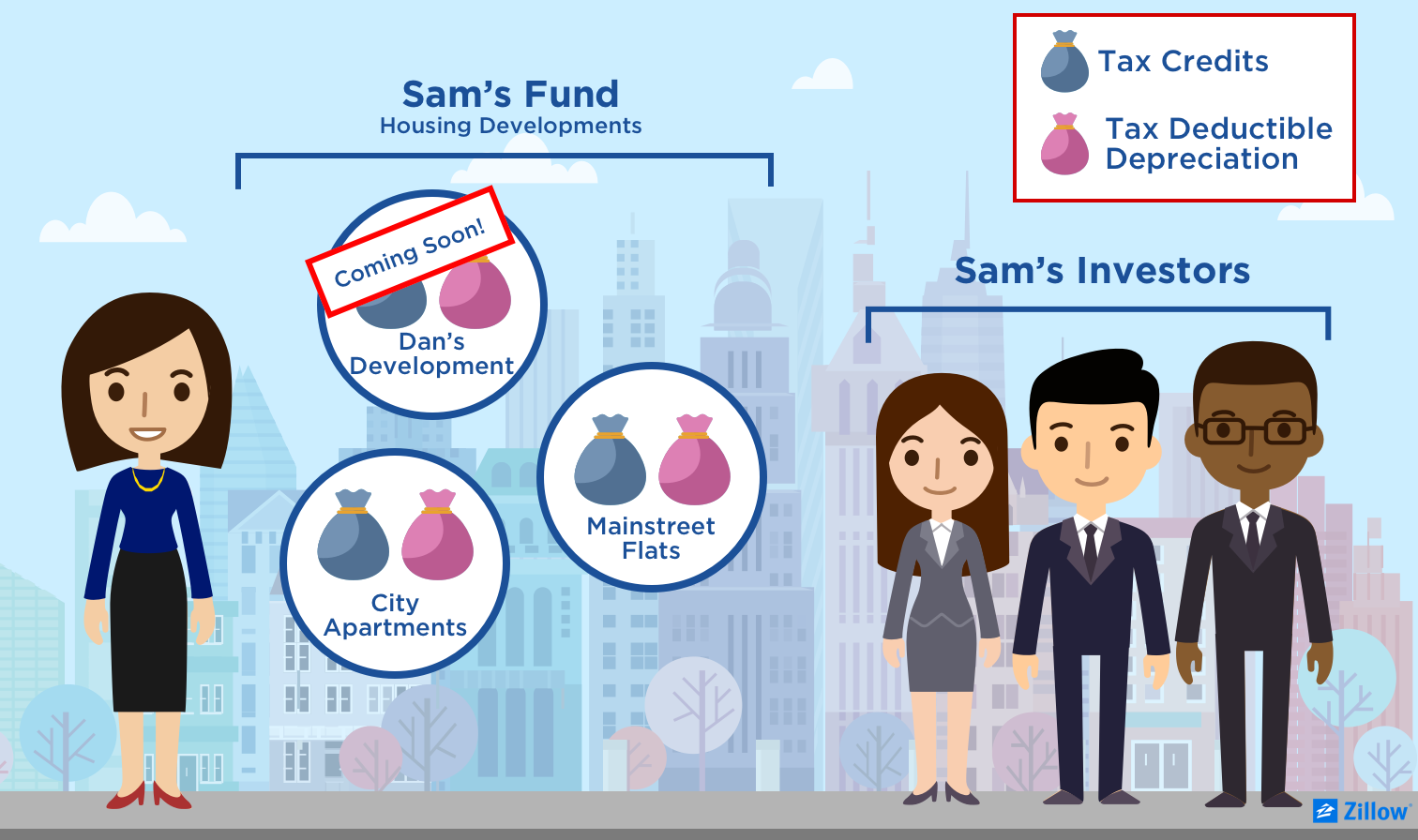

- Meanwhile, Sam the Syndicator is looking for investors for Sam’s Fund. By combining multiple LIHTC projects into one fund, syndicators offer an investment opportunity (85 percent of funding has historically come from the banking sector) to lower tax burdens that spreads risk and lowers the price of investing. For Sam’s Fund, investors pay 90 cents in order to buy $1 worth of tax credits and other real estate tax benefits. Sam is looking to add more LIHTC projects to her investment fund, so she meets with Dan.

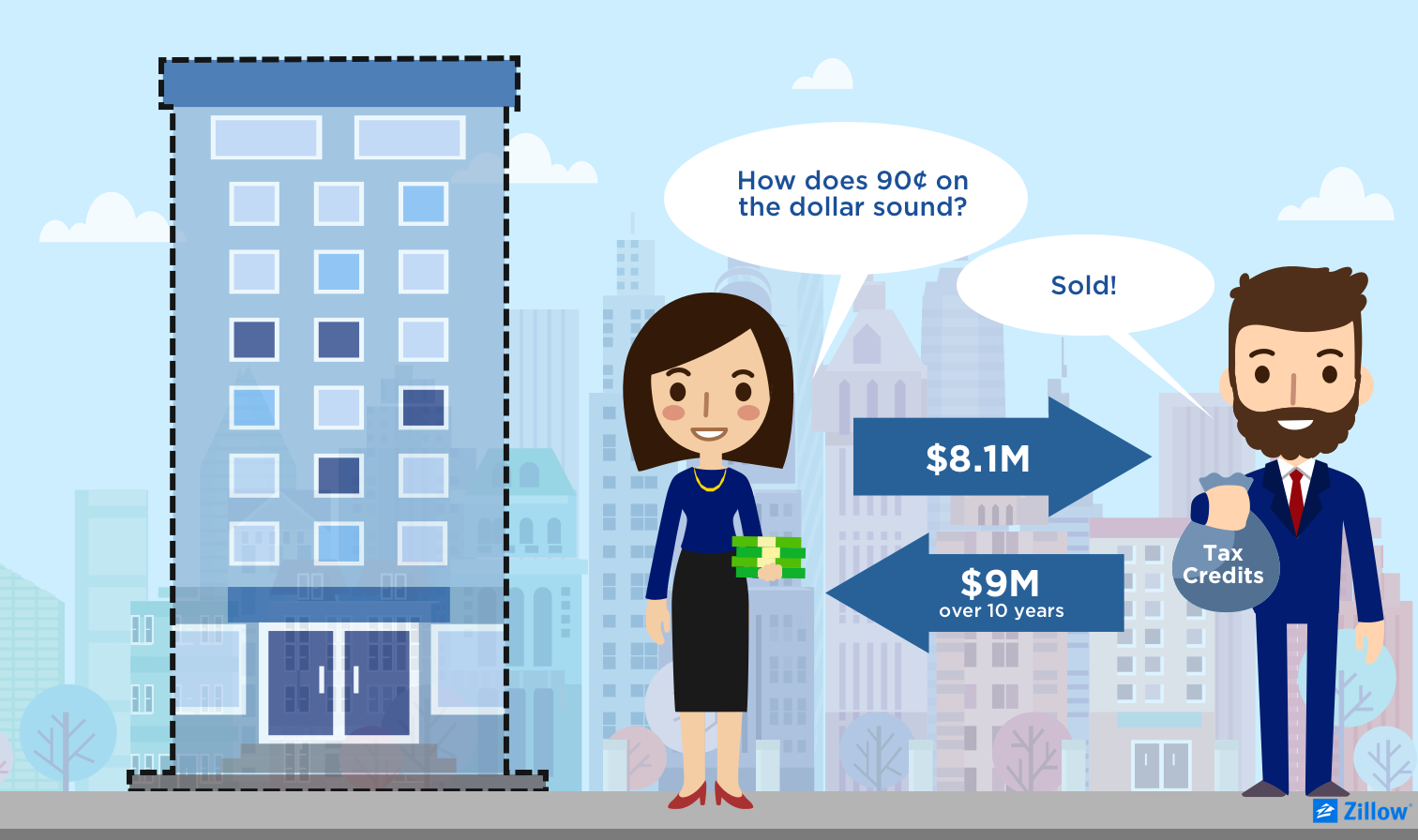

- Sam offers 90 cents on the dollar for Dan’s LIHTCs. Dan agrees, and sells his $9 million in credits that pay out over 10 years for an $8.1 million lump sum.

- Dan combines the $8.1 million from selling LIHTCs with other funding sources to reach the $13 million he needs. Because the value of the credits often doesn’t fully cover the entire construction cost, LIHTC projects frequently rely of a patchwork of funding sources in order to make ends meet. Additionally, the credits can’t be used until qualified tenants actually occupy the units, so developers like Dan must seek bridge loans or other funds to pay for construction up front before the LIHTCs have any value.

- Fast-forward one year, and Dan has secured all necessary funds, built his development, and rented all the units. The tax code allows owners of rental property or investors like Sam’s Fund to deduct the cost of the building from their taxes, but not all at once. This is known as “depreciation,” but not in the same way we often talk about housing values appreciating or depreciating. Given the cost of Dan’s building and the IRS’s rules, almost $475,000 worth of depreciation can be claimed by Sam’s Fund in addition to the $900,000 from LIHTCs for the first year. So long as Dan’s property remains eligible for the credits, Sam and her investors are set for 10 more years of this arrangement.

- LIHTC projects are required to keep the units priced at the determined “affordable” level for 30 years. If this agreement is broken within the first 15 years, the IRS can take back the value of the tax credit from investors. Beyond that, it’s up to the state HCA to enforce units are properly rented. Because the credits can be used for only 10 years, sometime between 10 and 15 years into the project, investors like Sam’s Fund often sell their ownership claim and move on to other investments. After year 15, Sam is gone and Dan is essentially a conventional landlord, collecting rents (capped at a certain amount) and maintaining his property.

Are they working?

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit program has undoubtedly contributed some amount of affordable housing that would not have otherwise been achieved in the free market without the government stepping in. However, the extent of that impact is subject to debate, and LIHTC projects are not without criticism. Like all government programs, there are times when it is the best tool for fixing a problem, and other instances where it is used despite other, more effective tools.

Here’s what critics and advocates have said:

Criticism

Praise

- Giving money to low-income families for housing doesn’t always help if rental housing is scarce and/or if property owners raise rents faster than vouchers can keep up. LIHTC increases the supply of housing to some degree, somewhat mitigating this problem.

- Alternatives like vouchers are limited, and some populations – including large households, singles and the elderly – have a more difficult time using those vouchers. Programs that actually build affordable housing are useful for these groups.

- Some research finds LIHTC properties can increase property appreciation on nearby blocks when located in low-income or blighted neighborhoods.

- Although sometimes priced similar to market-rate units in the area, LIHTC units are often higher quality.

- LIHTCs are enjoyed by the construction industry, which claims LIHTC projects provide additional business.

- Whether or not it was the most direct route to get there, to date at least 2.8 million households are now in homes that likely would not exist or likely priced more expensive without LIHTCs.

Why do they matter right now?

The recent tax proposal from the White House that would reduce the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 15 percent also would presumably lower the value of, and hence demand for, LIHTCs. Some estimates suggest as much as 17 percent of money raised through LIHTCs could disappear as credits lose value. If investors pay less in taxes after tax cuts, they won’t see as much value as they did before in a credit that lowers their taxes. Even without enacting corporate tax cuts, the mere speculation around a lower corporate tax has already affected LIHTC programs.

A devaluing of LIHTC could come at tenuous time for affordable housing providers and tenants. On the other side of the federal government’s ledger, the Trump Administration’s preliminary budget proposal includes steep cuts to housing assistance programs, making LIHTCs arguably an even more important funding option than before.

How might LIHTC change?

In response to decreasing affordability for renters as well uncertain government funding at all levels, activists and policymakers are working to protect LIHTC funding, while improving some of the program’s shortcomings.

One high-profile proposal is the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act of 2017 (a remixed version of a 2016 bill) championed by Senators Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of at least a dozen other Senators. It would rebrand the credit as an “Affordable Housing Credit” and expand its funding by raising the cap on credit allocation by 50 percent. The proposal also provides flexibility by allowing properties to average income limits across all its units. For example, 20 percent of units would need to be set aside for tenants whose incomes average 50 percent of AMI, as long as no renter earns more than 80 percent of AMI when they move in. In addition to these reforms, the bill pushes for a variety of tweaks to the administration of LIHTC and its eligibility requirements, including:

- A permanent minimum rate for the 4 percent credit

- Modifications to the costs that can be included in the eligible base

- Permission for states to boost the eligible base by 50 percent for developments targeting homeless communities or extremely low-income renters

- An expansion of the areas where developments can receive an eligible base boost for building in high-poverty areas

- New incentives for tax credit development in Native American communities

Related:

[1] The credit rate hasn’t always been exactly 9 percent, either. The specific rate was set so the present value equaled 70 percent (30 percent for the 4 percent credit) of certain construction costs over the 10-year life of the credits. The exact percentage used to arrive at a 70 percent subsidy over 10 years fluctuated over time. The 9 percent credit has ranged between 7.89 percent and 9.27 percent. In 2015, the 9 percent rate became permanently fixed at 9 percent, but the 4 percent credit still fluctuates with market conditions.