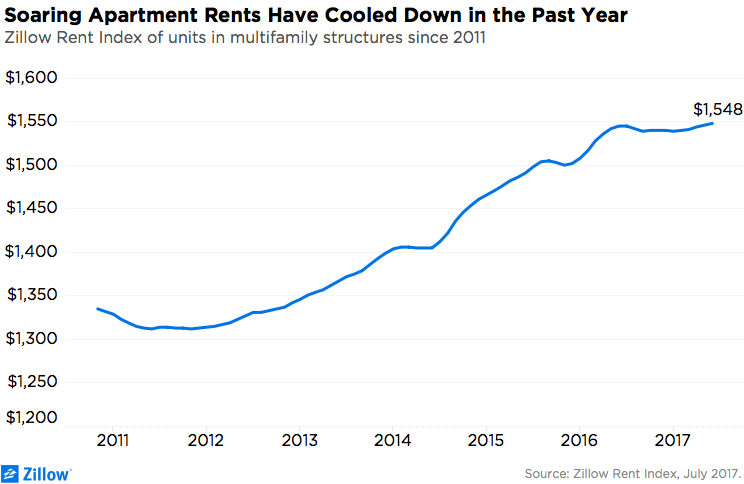

- Nationally, rents in multifamily structures have stagnated for the past year and will continue to do so as more new units become available in the coming months.

- Vacancy rates are still at historic lows after dropping every year since 2009 until recently, and landlords are offering rent concessions to keep it that way.

- In the longer term, we expect increased demand for rentals from three key demographics: Younger millennials entering prime renting age; older millennials that might typically buy homes but that are finding it harder to save a down payment; and an aging Baby Boomer population looking to downsize and potentially move to renting.

A recent surge in apartment construction could mean opportunities for renters to save some money over the next few years as more supply continues to come online and landlords compete to fill vacant units – especially at the higher end of the market. But looking farther out, that dynamic could reverse as a handful of demographic and economic trends take hold.

Younger millennials are just now entering prime renting ages, even as older millennials find it more challenging to save for a down payment and transition into homeownership – keeping them renting ever longer. Additionally, the large Baby Boomer generation is aging into a period of their lives in which selling their home, downsizing and/or renting is seemingly becoming more common. These shifts point to a significant growth in rental demand in the longer-term, with landlords poised to benefit.

Bearish in the Short-Run

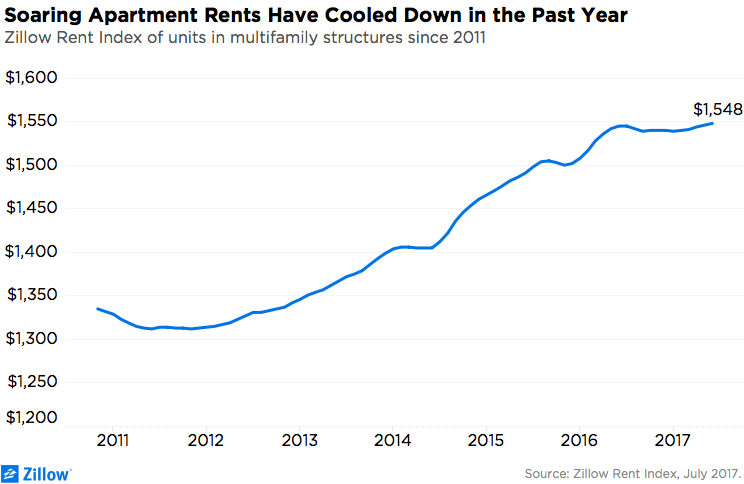

Renters living in multifamily complexes have gotten a bit of a reprieve from relentlessly rising rents this year. Rents in multi-family structures have stayed roughly constant over the last year after showing consistent growth over the past five or so years.

Renters living in multifamily complexes have gotten a bit of a reprieve from relentlessly rising rents this year. Rents in multi-family structures have stayed roughly constant over the last year after showing consistent growth over the past five or so years.

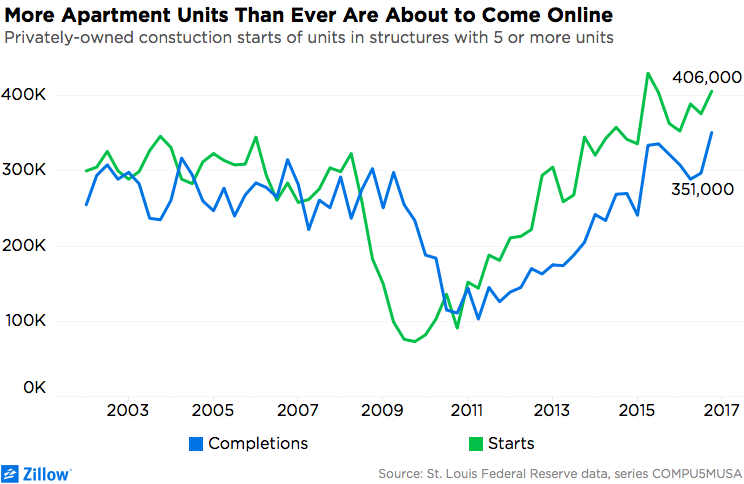

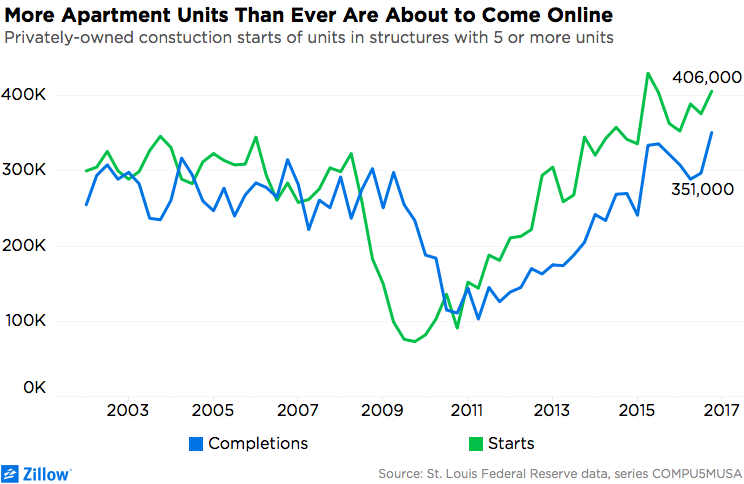

It typically takes 18-24 months for multifamily housing developments to be completed after construction begins, which likely means the glut of units started in early 2015 are starting to open for occupancy today. The rate of completions looks set to reach a multi-decade high in 2017, and this added supply is a boon for renters looking for tempered rents – more supply means more vacancies and slower rent growth.

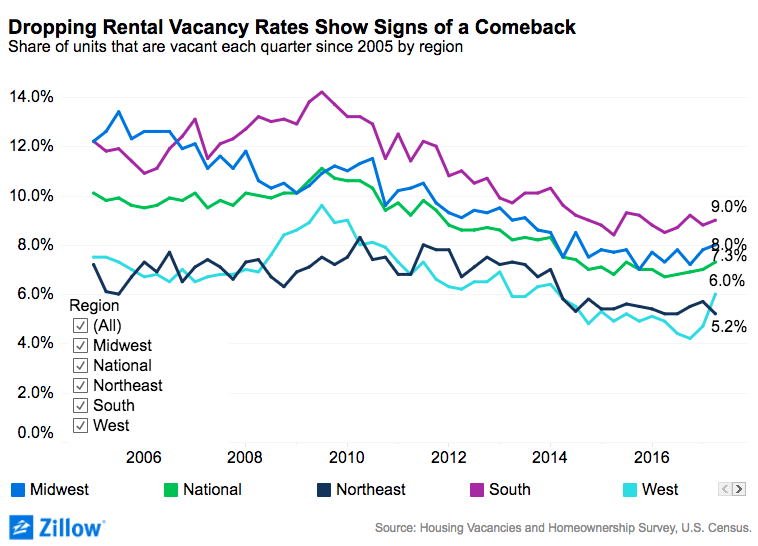

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, vacancy rates are well below their 2009 high. As of Q2 2017, the national vacancy rate stood at 7.3 percent, down substantially from its recent peak of 11.1 percent in Q3 2009. The precipitous drop in vacancy rates can be explained at least in part as a reaction to the foreclosure crisis – one-time homeowners foreclosed upon during the Great Recession were forced to move into rental housing, driving vacancy rates down and rents themselves up.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, vacancy rates are well below their 2009 high. As of Q2 2017, the national vacancy rate stood at 7.3 percent, down substantially from its recent peak of 11.1 percent in Q3 2009. The precipitous drop in vacancy rates can be explained at least in part as a reaction to the foreclosure crisis – one-time homeowners foreclosed upon during the Great Recession were forced to move into rental housing, driving vacancy rates down and rents themselves up.

But that has started to change more recently – likely because of the extra supply created by the flurry of multifamily construction activity. As of Q2 2017, the national rental vacancy rate has risen for five straight quarters, at the same time as rent growth has slowed.

The increasing rate of starts of multifamily structures (especially the spike in 2015) will lead to continued new rental supply over the short term. This means the trend of leveling vacancy rates and slower rent appreciation should continue. Zillow expects the U.S. median multifamily rent to appreciate just 2 percent over the next year (June 2017-June 2018), well below annual growth rates of more than 6 percent seen as recently as mid-2015 and below the historical average of 3.5 percent.

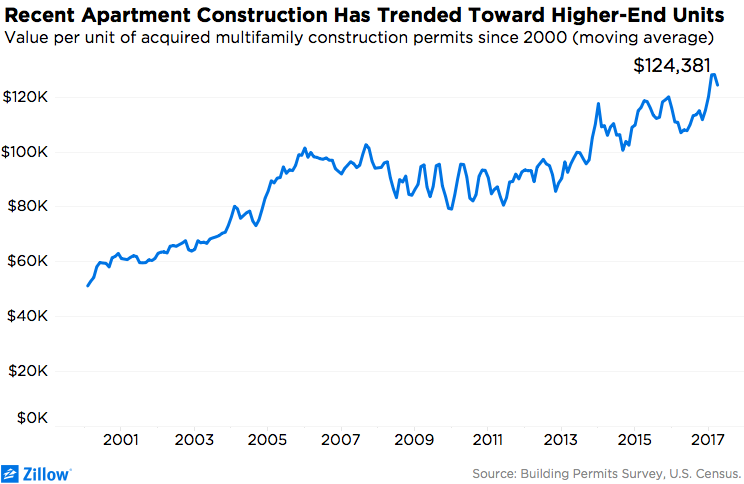

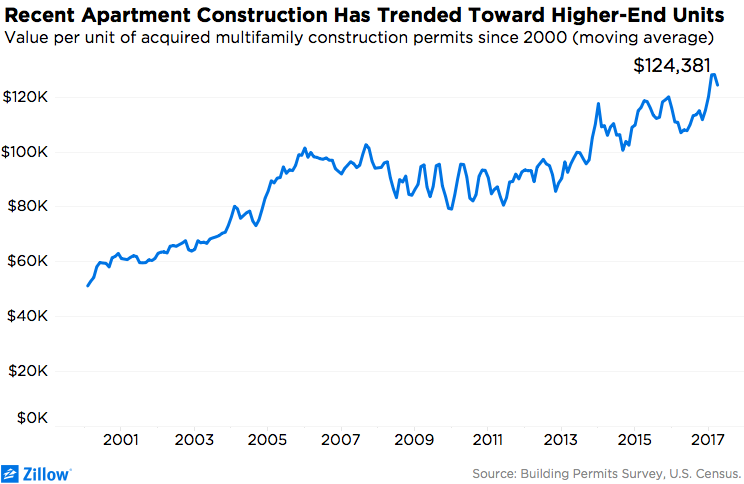

But there is a disconnect between the type of new rental units set to enter the market, and where rental demand is likely to come from. Last year, we found that rents for the cheapest apartments have been growing at a faster rate than the overall market. We largely attributed this to a lack of new supply at the lower end in the face of significant demand for cheaper apartments. Since 2014, apartment construction has skewed heavily towards the high end. In residential structures with five or more units, construction permit data shows that the value per unit being built has been steadily trending up.

But there is a disconnect between the type of new rental units set to enter the market, and where rental demand is likely to come from. Last year, we found that rents for the cheapest apartments have been growing at a faster rate than the overall market. We largely attributed this to a lack of new supply at the lower end in the face of significant demand for cheaper apartments. Since 2014, apartment construction has skewed heavily towards the high end. In residential structures with five or more units, construction permit data shows that the value per unit being built has been steadily trending up.

Rental vacancy rates are low overall, but particularly low among the least-expensive rentals, according to the Census Bureau. For units costing less than $300/month, the vacancy rate is a stunningly low 2 percent, and in the $300-$349/month range, it is at 4.6 percent – both much lower than the overall national figure of 7 percent as of Q2 2017. But it’s a totally different story at the high end: The vacancy rate for units renting for more than $1,500/month stands at 8.4 percent.

Because higher-end units rent for more money, vacancies in this segment cost landlords more in potentially lost revenue. One tactic landlords traditionally use to keep vacancies low is to offer a concession or special offer on signing – including a month of free or reduced rent, discounted or free parking and/or waived fees. If spread across a lease, a concession such as one month of free rent can go a long way, often enabling a tenant to effectively pay hundreds of dollars less per month. For example, a month of free rent on an apartment advertised at $2,400/month, spread across a 12-month lease, means effective rent can be reduced to $2,200/month, or savings of $200/month in actual rent paid. This strategy allows landlords to lower effective rent without lowering the advertised/actual rent as stated on their lease – which may upset current tenants paying higher rents.

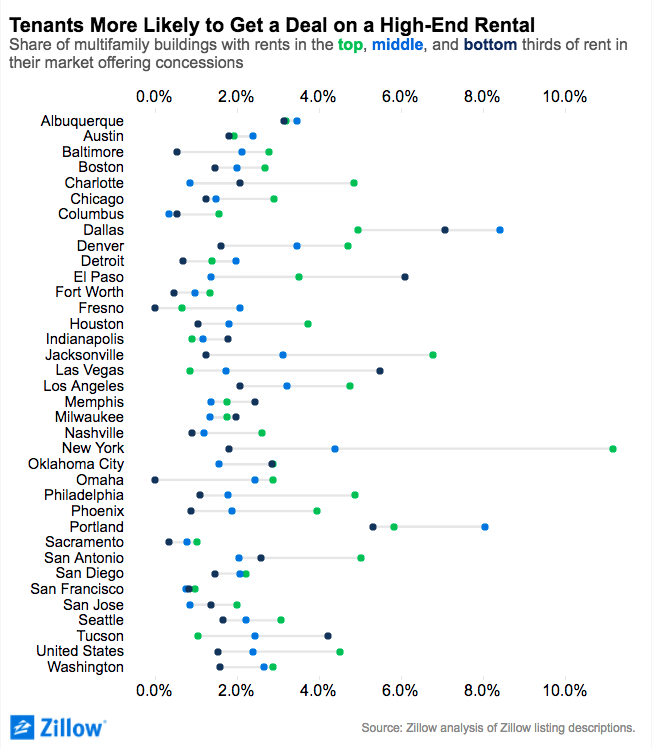

A New York City-specific analysis by StreetEasy.com Senior Economist Grant Long showed that rent concessions in the city are trending up, and are far more common among newer apartment structures. And growth in the overall U.S. rental housing stock has skewed significantly towards the higher end in the past decade. Combined, this suggests concessions would be much more common among rentals at the higher end of their respective markets. Zillow’s analysis of hundreds of thousands of listing descriptions nationwide shows this to be true.[1]

Nationwide, listing descriptions for apartments at the higher end of the market are three times more likely to mention concessions than listings at the lower end. This might be explained by the variability in vacancy rates at the bottom, middle and top of the market. Super-low vacancy rates at the bottom give landlords little incentive to offer a concession, especially with rent so low to begin with.

There is also a lot of variability from market-to-market in the rate of concessions. Some cities, like New York, have a stronger culture of concessions, so landlords more readily advertise them publicly. In other markets, it is more common for landlords to offer concessions verbally, making it harder to track. This is done to avoid the appearance of discounts that might publicly devalue their property or upset current tenants that may not have been offered a given deal.

In previous analyses, Zillow found that rent affordability is a particularly pressing issue for low-income households – the percent of income needed to afford rent for those low-income renters seeking a low-end apartment lowest third of rentals is increasing at a much quicker pace than for those in the middle and top segments. We also found that one way to save on rent was to not move, since rents charged upon renewing a lease tend to be lower than those charged on the open market at a different property. As such, it should come as no surprise that vacancy rates and concessions at the bottom are so low – there’s little incentive both for current tenants to move and for landlords to sweeten the deal.

Bullish in the Long-Run

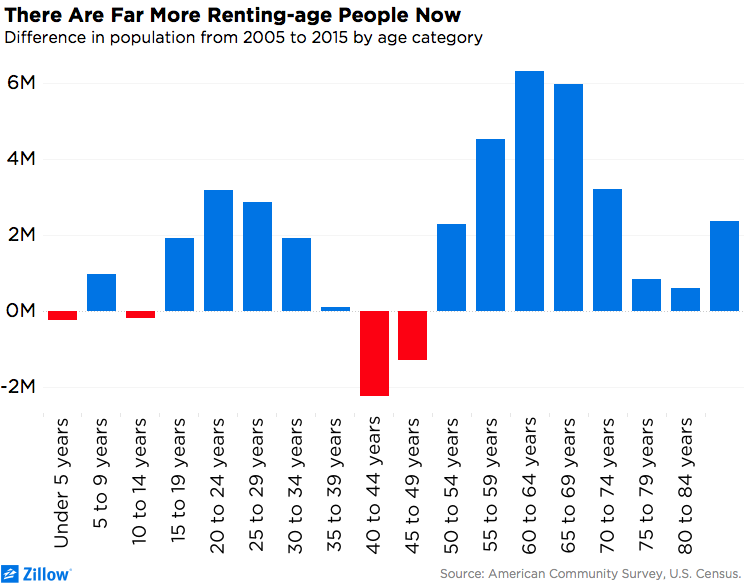

But the overall rental market picture changes dramatically when broadening the horizon and looking beyond the short term. Longer-term demographic trends should prove to be a tremendous tailwind for landlords and the rental market in the coming decade. Two generations in particular – Millennials and Baby Boomers – likely represent a ready source of future rental demand.

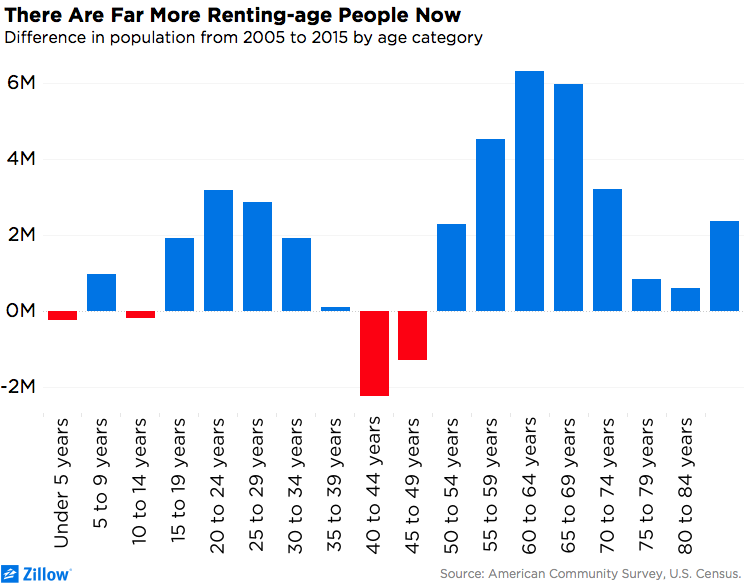

Historically, Americans are more apt to rent in their 20’s and early 30’s, and the current cohort of people aged 20-to-34 is the largest in recent memory. This age group has grown from 58 million people in 2005 to 66 million in 2015, a 14 percent increase, according to the American Community Survey. In comparison, the overall population of the United States grew only 11 percent over the same time period. On top of this, the aforementioned rent affordability issues often keeps renters renting. Avocado toast-related comments aside, millennials have trouble saving for a competitive down payment when their rent burden is already so high.

But while we may tend to think of apartment hunting as a young person’s game, we can’t count out the potential silver boom in the rental market. Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies recently found that 44 percent of all renter household growth from 2005 to 2016 has come from households headed by someone over 55 years old, increasing their share in the market from 22 percent in 2005 to 27 percent.

This finding is also echoed in national homeownership rate statistics. If you don’t own a home, you very likely rent one, and the homeownership rate among those aged 55-to-64 has fallen considerably over the past decade, from more than 80 percent in 2004 to roughly 75 percent by the end of 2015. Some of this decline is, again, likely attributable to the foreclosure crisis turning former homeowners into renters. And yes, three-quarters of Americans nearing retirement age do still own homes, a rate well above the overall national rate. But the fact that the decline in homeownership in this group both began prior to the Great Recession and has persisted well after it ended suggests at least the possibility that many of these older Americans are choosing to rent out of preference and maybe not out of necessity.

These longer-term demographic trends will serve as big-time boons for landlords. Freddie Mac estimates that “several million” home-owning boomers will become renters by 2020, and the National Multifamily Housing Council, an apartment industry lobbying group, insists that there will be a shortage of over 1.5mm apartments by 2027. That said, in the short-term, renters can look forward to more moderate rent increases and opportunities for discounted rent as new supply peaks in the next one or two years.

[1] The analysis was conducted by algorithmically searching the text of hundreds of thousands of rental listing descriptions on Zillow and its subsidiary brands to detect natural language that offers a concession.