Editor’s Note: April 11, 2018 marked the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the landmark Fair Housing Act, which now prohibits housing discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, familial status and/or disability. While a lot has improved, there is still much progress to be made toward ensuring true equality in housing. For this post, we talked to locals in three places where home values in formerly redlined areas have passed the values in some other neighborhoods. The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the views of Zillow. We invite you to read all of Zillow Research’s related research and analysis.

St. Louis: ‘Things Haven’t Changed That Much’

Home values in historically redlined parts of St. Louis are worth more now than values in some areas that were deemed less “hazardous” for lending 80 years ago. It’s a trend that bucks the picture in many other redlined communities across the country – but that doesn’t mean St. Louis has overcome its legacy of housing discrimination any better than areas where home values in redlined neighborhoods remain lower.

“That in no way means the basic underpinnings – racism and a lack of access to credit – have changed at all,” said Glenn Burleigh, community engagement specialist for the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council. “The market is highly racialized.”

The neighborhoods have changed and boundaries have shifted, but in the bigger picture, he said, “Things haven’t changed that much.”

For one thing, many homes in formerly redlined neighborhoods of St. Louis are gone now, paved over by highways, malls and an airport expansion, he said.

Of the homes remaining, many are Victorian mansions abandoned by white people during the white flight that accompanied redlining in many parts of the country. Some were segmented into multi-family dwellings. Now that inner cities are popular again, well-to-do white people have returned and restored those mansions to their original glory – often by reconverting them into single-family homes.

African Americans now are clustered in neighborhoods north of Delmar Boulevard – also known as the “Delmar Divide” – where getting a mortgage remains “in many ways harder than it was 20 years ago,” Burleigh said.

“We have spent enormous sums of public money to spatially reinforce human segregation patterns,” Michael Allen, director of the Preservation Research Office told St. Louis Magazine. “We have harnessed architecture as a barrier. And it’s been very frightening to see the result.”

Writer and educator John Wright, in the same article, said a few neighborhoods deliberately desegregated. For those that didn’t, unfamiliarity with people of other races has bred fear – and worse.

“You’ve still got people who won’t even go to Forest Park – they read somewhere that someone got raped in 1901,” he told the magazine.

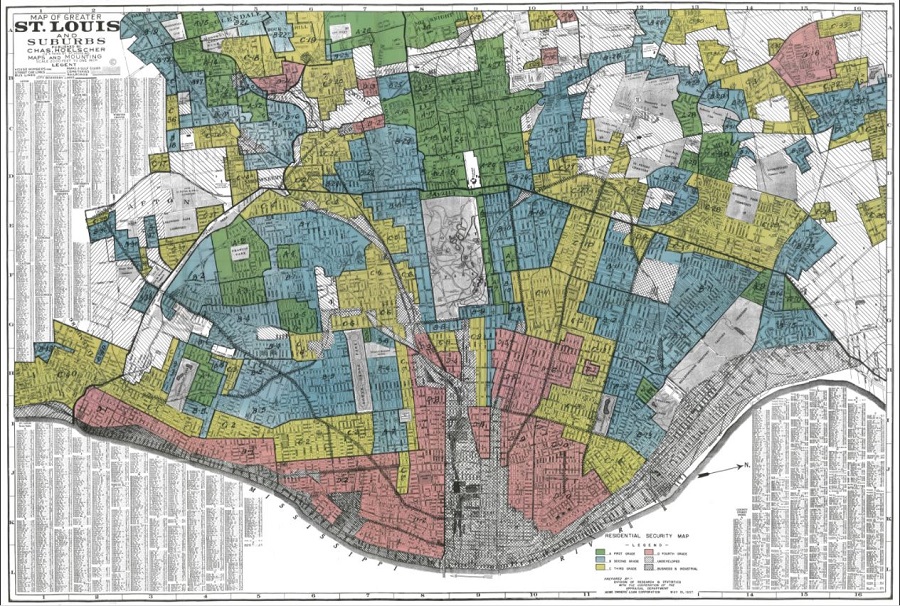

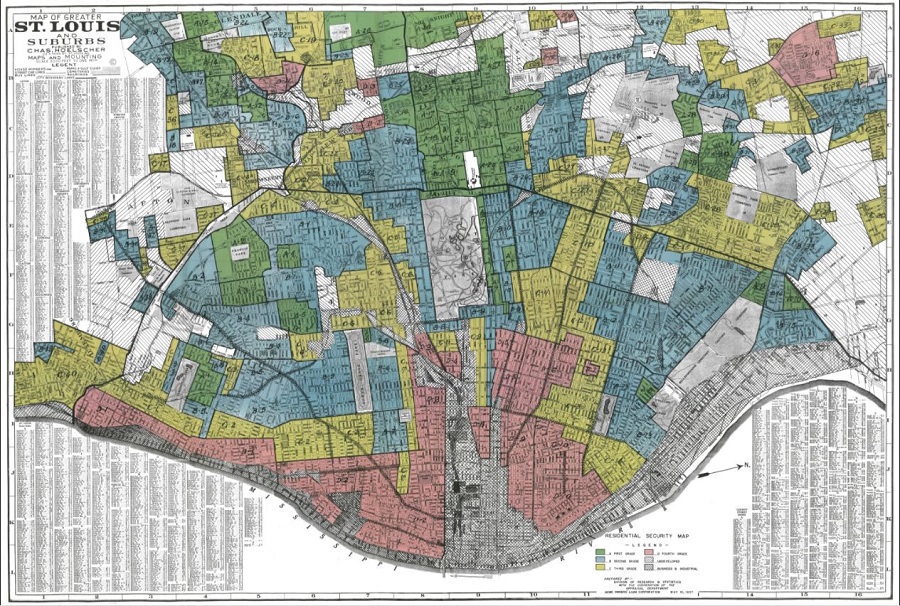

A redlining map of St. Louis from Mapping Inequality, a project of four universities led by Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly and others. Click on the map to link to the full project.

Philadelphia: An Influx of Wealthy Newcomers

“Being the poorest big city in the U.S. complicates our status as this inexpensive city on the East Coast,” Philadelphia journalist and radio host Charles Ellison explains when he hears that home values in formerly redlined neighborhoods there are doing better than some non-redlined parts of the city.

Indeed, Philadelphia is affordable. A household earning the median income there pays 14.8 percent of their income each month for the typical home, or 27.7 percent for the median rent – both below national averages.

That – and property tax abatements – make it attractive to outsiders, including well-paid New Yorkers and others who are willing to endure long commutes for a lower cost of living. To critics, abatement is a force for gentrification that’s making the city less affordable for locals.

And gentrification is one reason for the median home value in Philadelphia’s formerly redlined neighborhoods is now $285,539 – above the median for areas the government deemed “definitely declining” ($247,708) and almost in line with areas marked “still desirable” ($289,681).

Like historical redlining, modern-day gentrification is about race as well as money.

The Center for Investigative Reporting recently found that the greater the number of African Americans or Latinos in a Philadelphia neighborhood, the more likely a loan application would be denied – even after accounting for income and other factors.

Not all of Philadelphia’s historically redlined neighborhoods are flourishing: In the same report, the center found that Nicetown, where a government surveyor in the 1930s noted new industry, good transportation and a “heavy concentration of negro,” still languishes. Between 2012 and 2016, lenders made 67 home improvement loans there – and denied 315.

“Even what happened with Starbucks recently is seen as a symbol of gentrification and symbolic of the tensions,” Ellison said. During that incident, two black customers were arrested on suspicion of trespassing while they waited for a colleague to show up for coffee.

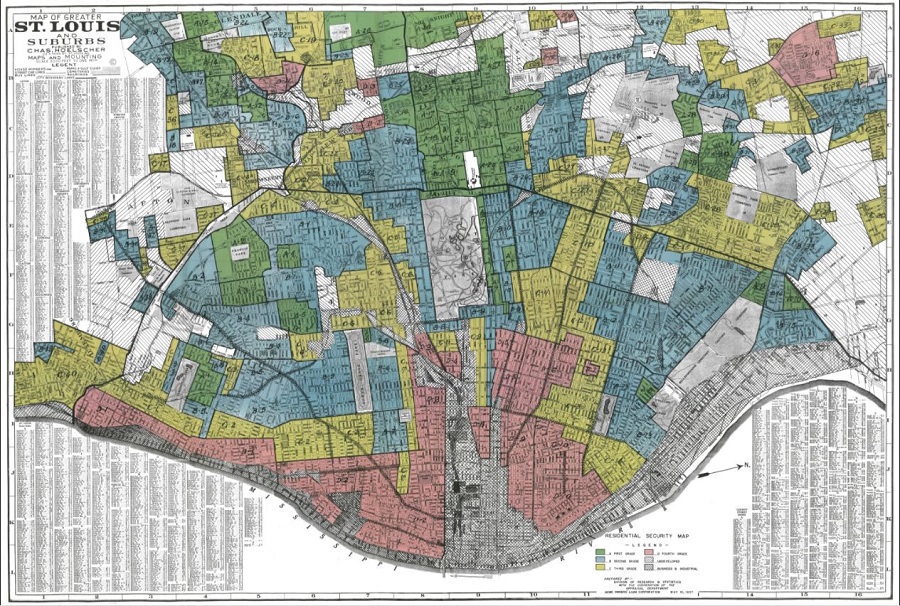

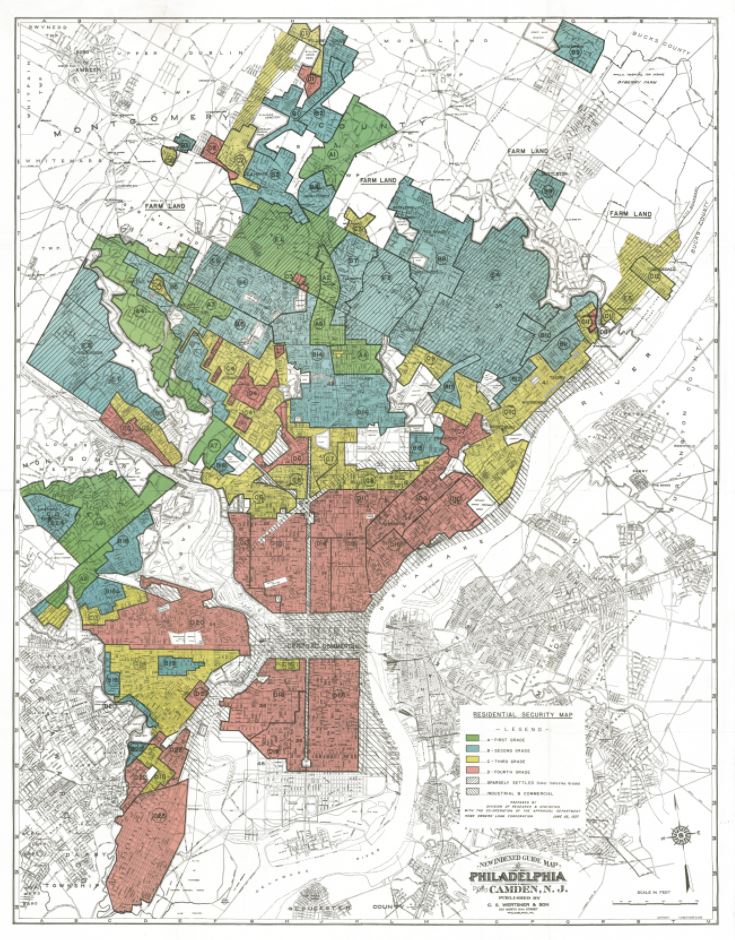

A redlining map of Philadelphia from Mapping Inequality, a project of four universities led by Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly and others. Click on the map to link to the full project.

Portland: An Early Start, and Displacement

The state of Oregon has a small black population, and only 5.7 percent of residents in Portland, its largest city, are black – compared with 12.1 percent of the U.S. population. It’s the only state whose constitution forbade blacks from living, working or owning property within its borders, although black people did all those things anyway. In fact, they were present in large enough numbers by the 1920s and 1930s that Portland neighborhoods were redlined in the same race-based ways as many other urban areas.

They also experienced the same consequences as redlined neighborhoods in cities with larger black populations: For example, redlined areas were cleared for a hospital, a highway and a coliseum, said Carl Abbott, professor emeritus of urban studies and planning at Portland State University.

However, the median home value in formerly redlined areas has been higher for at least 20 years than places the government labeled “definitely declining” in 1938. They are almost in line with areas that were rated “still desirable.”

One reason appears to be how quickly Portland stemmed the tide of the city’s urban decay.

“A lot of community activism prevented further decline and disinvestment” of the urban core, including redlined neighborhoods, Abbott said. “One of the keys was the strength of downtown Portland starting in the ‘70s with really strong efforts to prevent downtown from deteriorating.”

Compared to some other cities, Portland’s housing stock was easy to rehab, he said.

“Lots of homes built from 1910 to 1930 are modest but still have the basic capacity to be spiffed up and then added to. It was easier here than places like Philadelphia with a bunch of very narrow row houses that are hard to do much with.”

More recently, high housing costs have pushed people out of many parts of Portland, Abbot said. “It’s happened in a whole circle of neighborhoods, so it’s not as cataclysmic as having one neighborhood become trendy and everything changes in four years,” Abbott said.

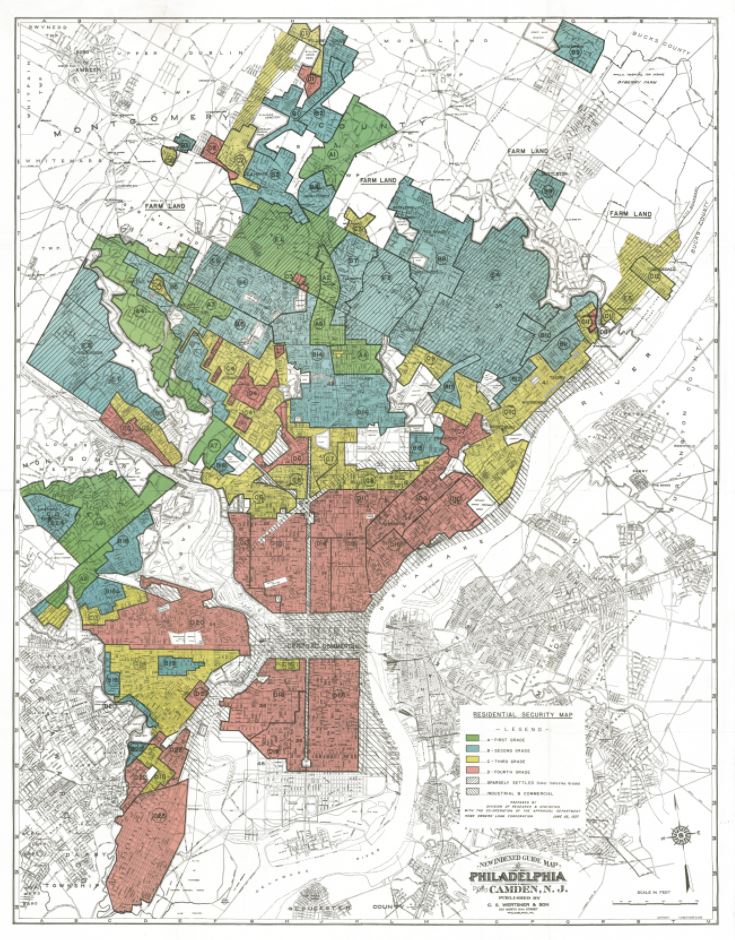

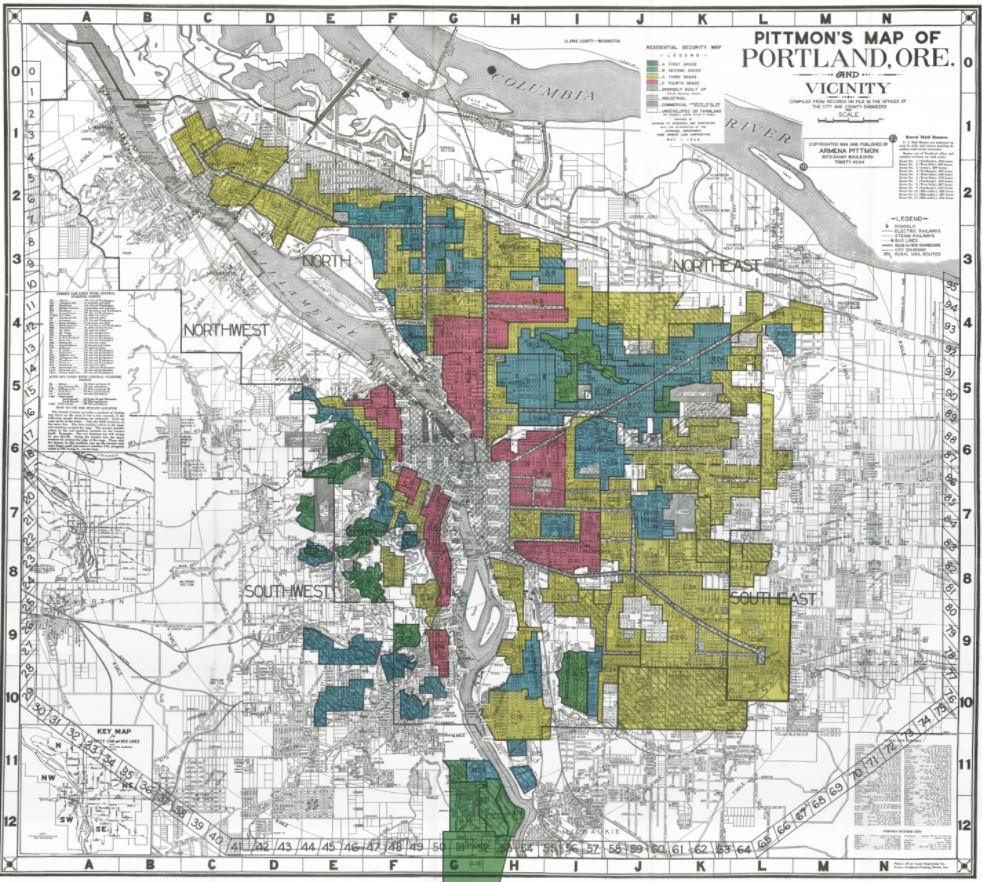

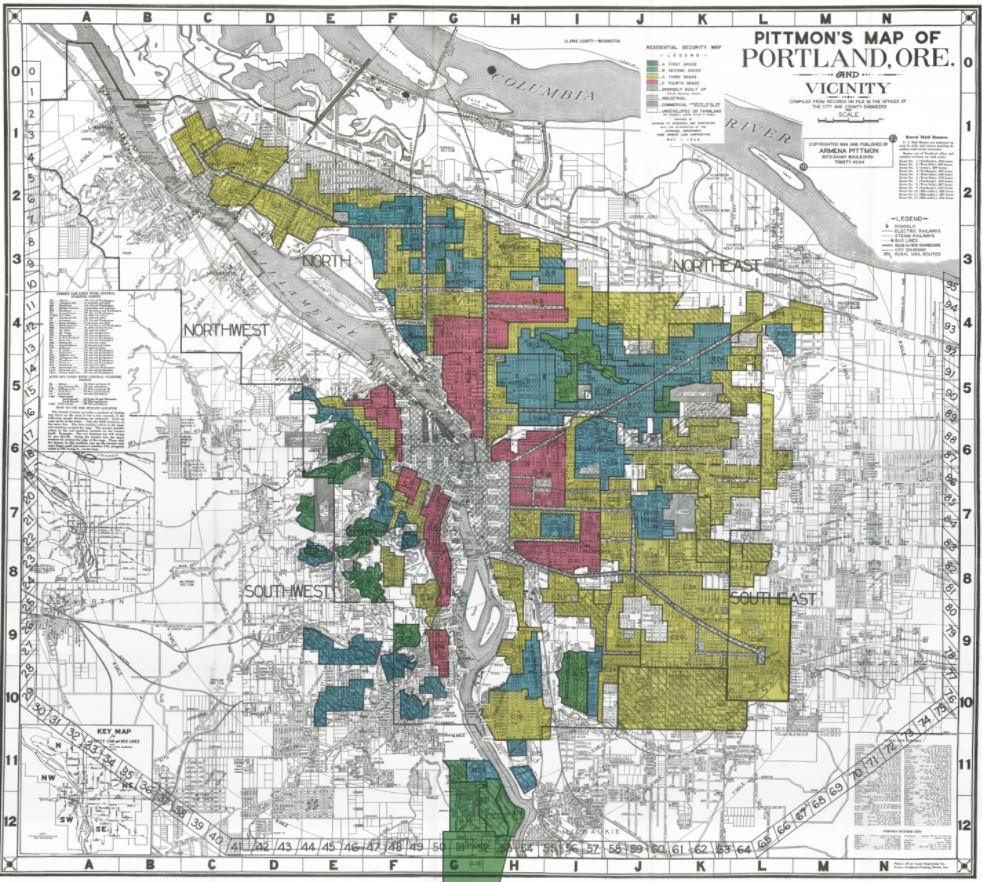

A redlining map of Portland from Mapping Inequality, a project of four universities led by Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly and others. Click on the map to link to the full project.