Close to Home: Why Stay-at-Home Parenting is Increasingly a Luxury

The share of U.S. children with a stay-at-home parent has plummeted since the 1970s, a result of changing demographics and social norms. With housing costs and child care among the two largest budget items for many working families, the shifts help explain both growing demand for child care and the evolving work-life balance of many U.S. families.

- The share of U.S. children with a stay-at-home parent has held steady since the mid-1990s, after falling sharply over the previous two decades.

- More fathers are staying home to care for their children, though they remain much less likely to stay home than mothers.

- Across the country, staying at home is least common among middle-income households and appears to be a luxury for the very highest income households, particularly in expensive housing markets.

The share of U.S. children with a stay-at-home parent has plummeted since the 1970s, a result of changing demographics and social norms. With housing costs and child care among the two largest budget items for many working families, the shifts help explain both growing demand for child care and the evolving work-life balance of many U.S. families.

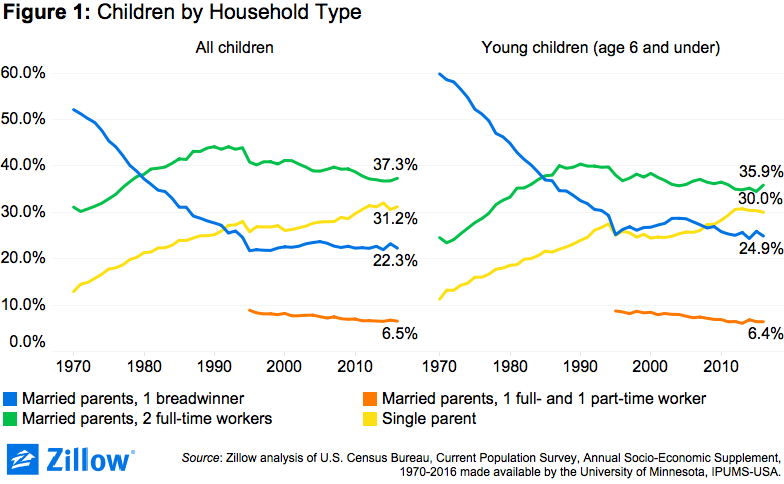

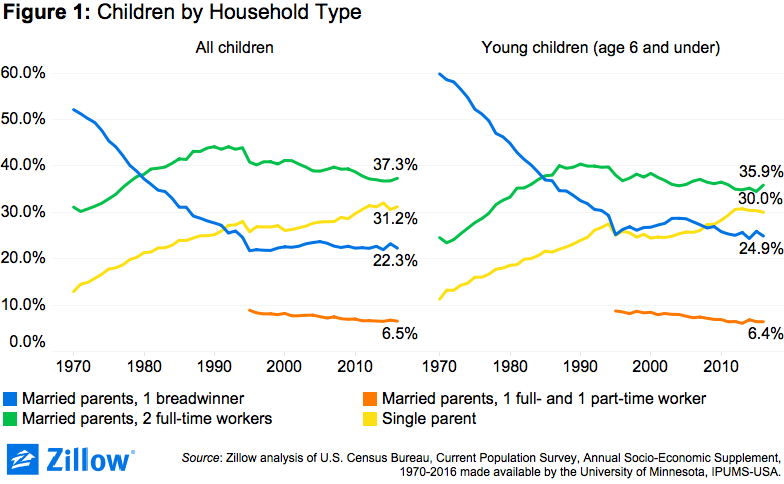

In 2016, almost one in four American kids (22.3 percent) lived in a household with two parents in which one did not work at all, according to a Zillow analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS). An additional 6.5 percent of children lived in a household in which one parent worked, but only part-time (figure 1, left). Among children aged six and under, the share with at least one full-time, stay-at-home parent was higher (24.9 percent), and was essentially the same (at 6.4 percent) for the share with a part-time, stay-at-home parent (figure 1, right).

Since the early 1980s, the largest share of U.S. children have had two parents employed full-time. Since the early 1990s (the mid-2000s for young children), children in single-parent households have been the second-largest group. The share of American children with at least one stay-at-home parent fell steadily from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, from 52.1 percent in 1970 to 21.7 percent in 1995, remaining roughly stable since. The share of young children with a stay-at-home parent increased from the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s, before retreating over the past decade. The share of children with one parent working full-time and one parent working part-time has been steadily declining since the 1990s.

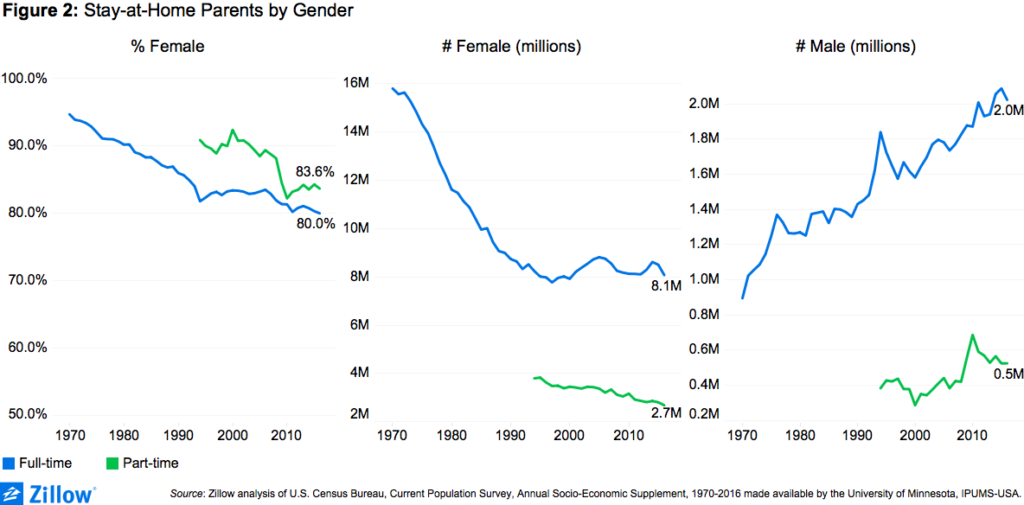

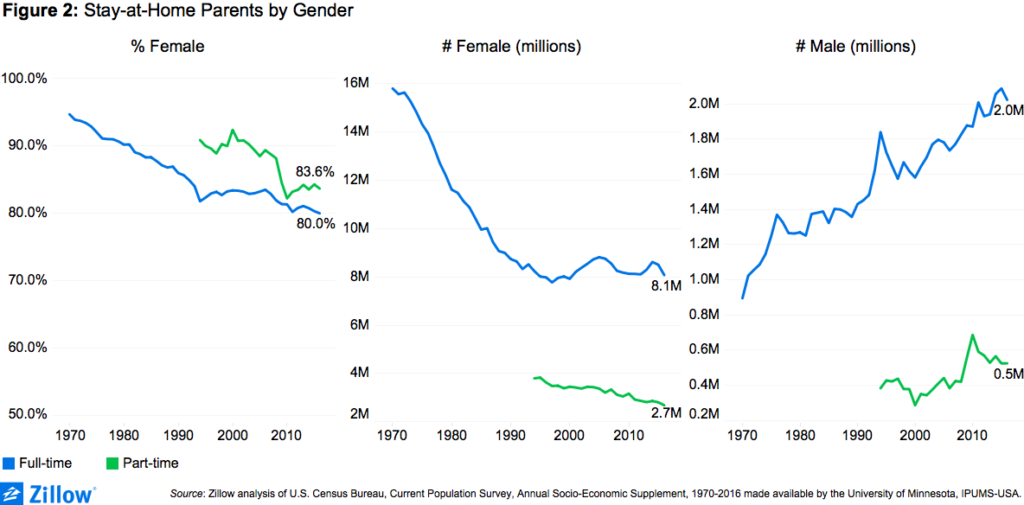

Historically, women accounted for the vast majority of stay-at-home parents, and while that’s still true, it is gradually changing. In 1970, women represented 94.6 percent of stay-at-home parents; by 2016, 80 percent of stay-at-home parents were women (figure 2). Put another way, almost one-in-five stay-at-home parents today is the father, compared to about one-in-twenty a generation ago. In 2016, there were 8.1 million women and 2 million men who were full-time, stay-at-home parents; an additional 2.7 million women and 500,000 men were part-time, stay-at-home parents. Since the mid-1990s, the number of female stay-at-home parents has largely held steady between 8 million and 9 million, despite population growth. Since the mid-1990s, the decline in the number of women who are stay-at-home parents has been driven by a decline in part-time, stay-at-home mothers.

Households in which both parents work full-time have higher incomes than households in which one parent stays at home full- or part-time. The median annual household income in 2015 of families with children where one parent stayed home full-time was $63,800; household income for families in which one parent stayed home part-time was $83,000. For families in which both parents worked full-time outside the home, median annual household income was $105,000.

Of course, it shouldn’t be much of a surprise that households with more workers have higher total incomes. But this conclusion also holds when looking only at the wage and salary income of the primary breadwinner – that is, the highest earning, full-time employed adult – in each household. The median wage and salary income in 2015 of primary breadwinners in families with children where one parent stayed at home full-time was $38,000, compared to $44,000 for families where one parent stayed home part-time. For households in which both parents worked full-time outside the home, the income of the primary breadwinner was $50,000.

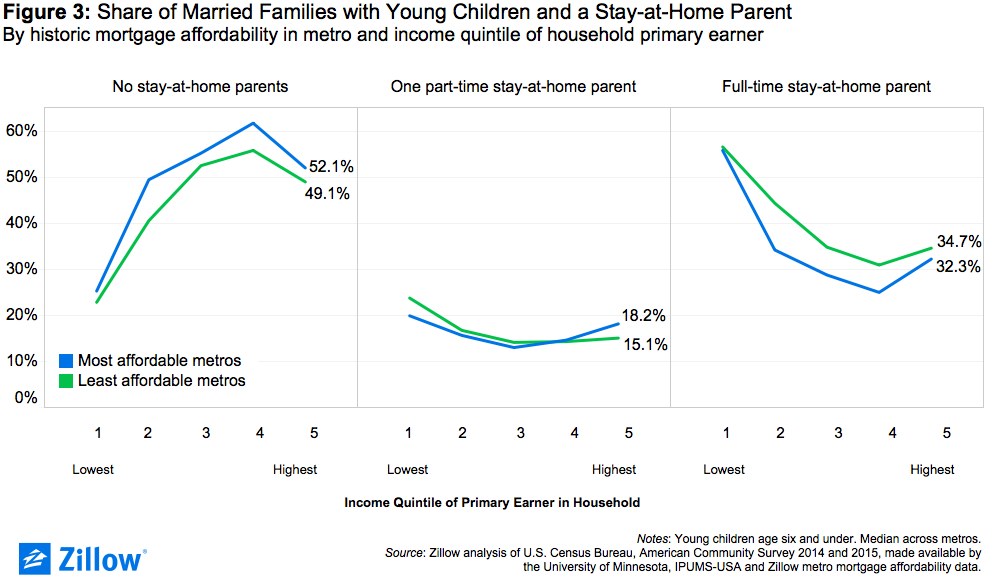

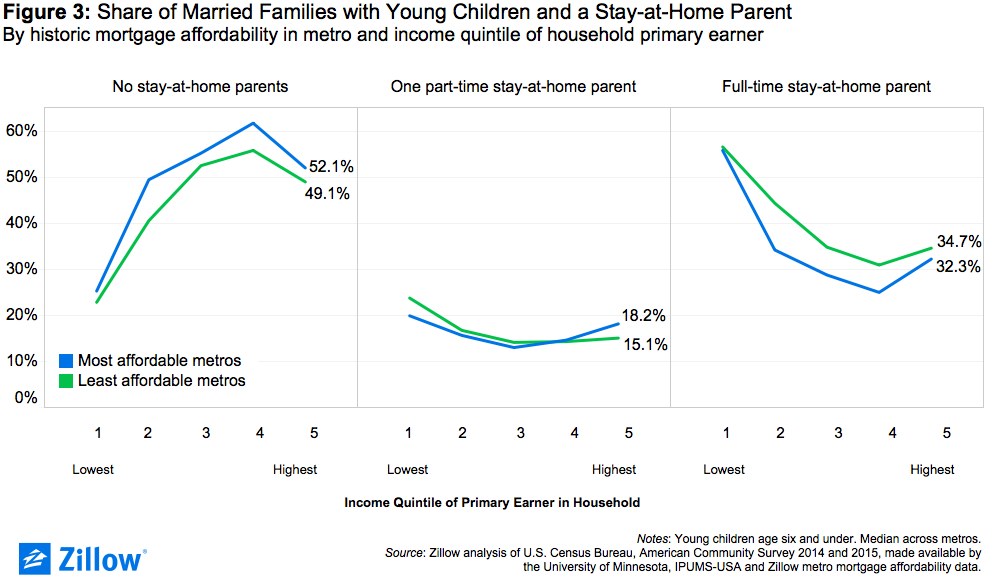

Overall, stay-at-home parenting does appear to be a luxury, particularly in expensive housing markets. Figure 3 shows the share of households with married parents and young children (age six and under) in which one parent stays home part- or full-time, grouped by:

- The income quintile of the primary earner in the household (relative to other primary earners in their metro area)[1]

- Historic mortgage affordability (the share of the typical household’s income that goes to a monthly mortgage payment) in their metro area.

In general, higher-income households – those households were the primary earner earns more relative to his or her peers – are less likely to have a stay-at-home parent. This is likely the result of selection: Better-educated, higher-earning adults are likely to partner with other well-educated, high-earning adults for whom quitting a job to care for children represents a substantial personal and professional sacrifice.

But this relationship breaks down for the very highest earners. The share of households with young children and married parents where a parent stays at home increases among the highest echelon of primary earners, suggesting the most affluent households are able to afford a stay-at-home parent. Additionally, the increase is, on average, sharper in metro areas where housing is more affordable compared to those where housing is expensive. In the most expensive parts of the country, a smaller number of even the best-heeled families with young children opt to or can afford to have a parent stay at home part- or full-time.

For many working parents, pursuing careers independent of their children is a personal choice beyond any financial motive. But across many metro markets, rising housing costs have made it impossible for some parents who would prefer to stay at home to afford to live on a single income. By pushing both parents into the labor market, these budget constraints increase demand for childcare services as parents struggle to balance work and family life.

[1] Households in quintile 1 have a primary earner among the lowest earners in the metro and households in quintile 5 have a primary earner among the highest earners in the metro.