Yes, First-Time Buyer Demand Is Weak. But Stop Blaming Student Debt.

Roughly 40 million Americans owe more than $1.2 trillion in combined student debt, enough to buy every property currently listed for sale on Zillow[1] and still have $375 billion left over. This high debt load has become part of the narrative for why millennials are delaying buying homes longer than any generation in recent memory.

More student debt means recent graduates will struggle to save a down payment, run into debt-to-income constraints when they apply for a loan and face credit ramifications if they default or miss payments. All of this will dramatically hurt their odds of successfully buying a home.

Or so the story goes. But in reality, that story may have some holes.

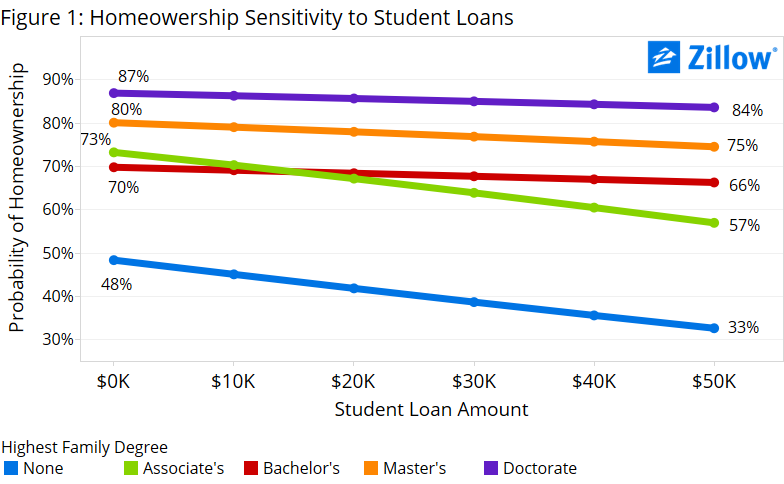

Zillow’s research[2] finds that, yes, student loans negatively impact a borrower’s predicted probability of homeownership. But the impact may be much smaller than imagined, especially if the borrower in question flipped their tassel to the right come commencement (i.e., actually finished school and graduated with a bachelor’s degree). Finishing with a bachelor’s degree or higher actually tends to insulate borrowers from being adversely affected by student loan debt when it comes time to buy (figure 1).

Zillow’s research[2] finds that, yes, student loans negatively impact a borrower’s predicted probability of homeownership. But the impact may be much smaller than imagined, especially if the borrower in question flipped their tassel to the right come commencement (i.e., actually finished school and graduated with a bachelor’s degree). Finishing with a bachelor’s degree or higher actually tends to insulate borrowers from being adversely affected by student loan debt when it comes time to buy (figure 1).

Our assumptions are based on a 33-year-old, married couple with children, with average income and accumulated wealth for someone with a given degree. For example, a 33-year-old family with at least one master’s degree between them and no student debt has a predicted probability of homeownership of 80 percent. If that same family had $50,000 in student debt, their predicted probability of homeownership falls by only 5 percentage points, to 75 percent. Households with a bachelor’s degree or doctorate see similar marginal effects. The impact for similar households with an associate’s degree or no degree at all is much starker, with their homeownership probability falling 16 and 15 percentage points, respectively.

What’s interesting about these findings is just how little student debt appears to matter when it comes to homeownership. If there was a clear relation between student debt and homeownership, we would expect to see more renter households relative to homeowners at higher levels of student debt. But we don’t. For households with a doctorate, master’s, bachelor’s or associate’s degrees, the proportion of buyers to renters remains relatively constant at varying levels of student debt.

But while the relationship between student loans and homeownership is seemingly nonexistent, age and income play a substantial role in homeownership. Homeowners are generally older and make more money. If you select all renters in the bottom graph by dragging over the points, and then do the same for homeowners, you will see that homeowners across all degrees tend to be older and make more money.

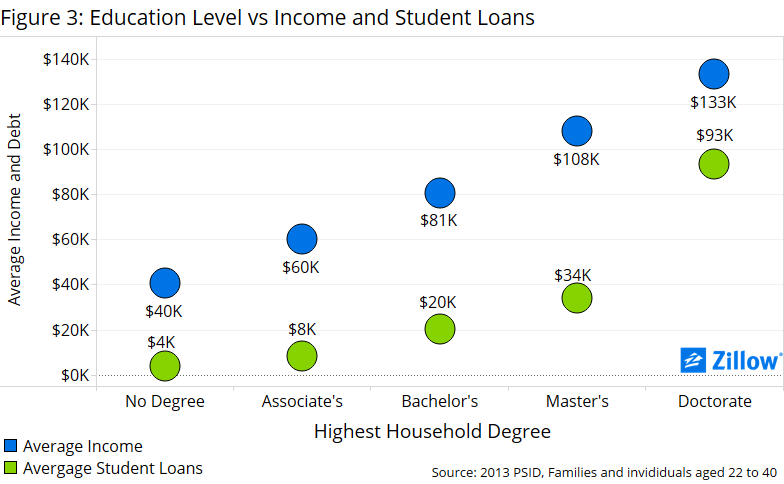

Given that the current narrative around student debt focuses on rising loan amounts and stagnant income, it’s important to control for income when looking at the impact of student loans. Figure 3 shows a not-so-surprising relationship: Households with a higher degree both make more and have more outstanding debt on average.

Given that the current narrative around student debt focuses on rising loan amounts and stagnant income, it’s important to control for income when looking at the impact of student loans. Figure 3 shows a not-so-surprising relationship: Households with a higher degree both make more and have more outstanding debt on average.

Ultimately the best way to control for income is to construct a model that controls for relevant variables. That’s why we constructed the model referenced earlier. The model specification predicts household homeownership based on student debt, and max degree earned[3], controlling for income, wealth, age, marital status, and whether the household has children. The model shows an adverse relationship between student debt and predicted homeownership, but again, the magnitude of the effect is not large for households with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

As student debt continues to rise, we can’t say this relationship (or lack thereof) between student debt and homeownership won’t change for the worse. But looking back historically, the relationship is not nearly as clear-cut as the common narrative would have us believe.

[1] The current price tag for every for-sale property on Zillow is a mere 823 billion dollars as of 9/10/2015.

[2] Zillow analyzed data from the 2013 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a biannual survey following generations of families since the late 1960s, tracking their socioeconomic conditions over time. In 2011, the PSID began asking specifically about student debt. For our analysis, we looked at families and individuals between the ages of 22 and 40 with non-negative income (3796 households in the 2013 PSID met this criteria). We then constructed a model predicting homeownership rates using student debt, controlling for highest degree attained, income, wealth (sans home equity and student debt), age, marital status and children.

[3] We included an interaction term between degree and student debt, as intuitively an extra $20,000 of student loan debt should effect the homeownership patterns of doctors less than someone with an associate’s degree.