Why is Home Buying Demand So High? Partly Because Buying Conditions (in Theory) Are So Good

An incredibly strong jobs market, coupled with historically high levels of home affordability, is helping create a perfect storm of home buying demand that is proving incredibly difficult for home builders and home sellers to satisfy.

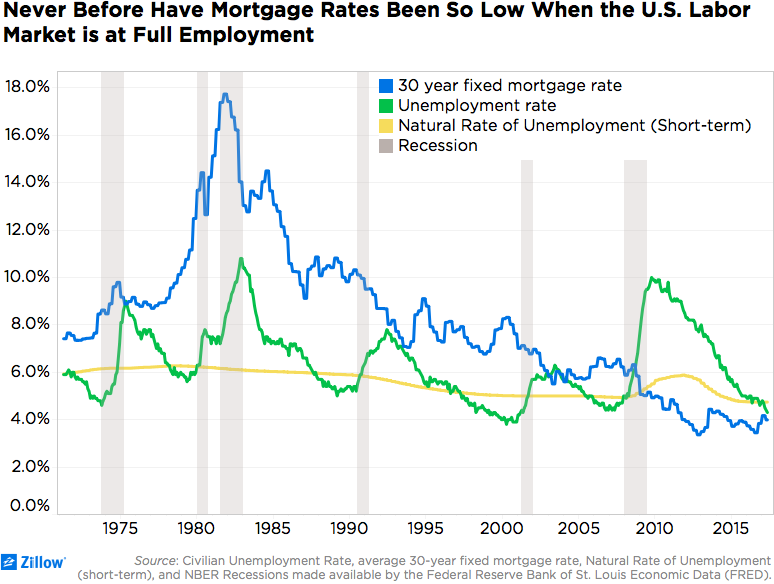

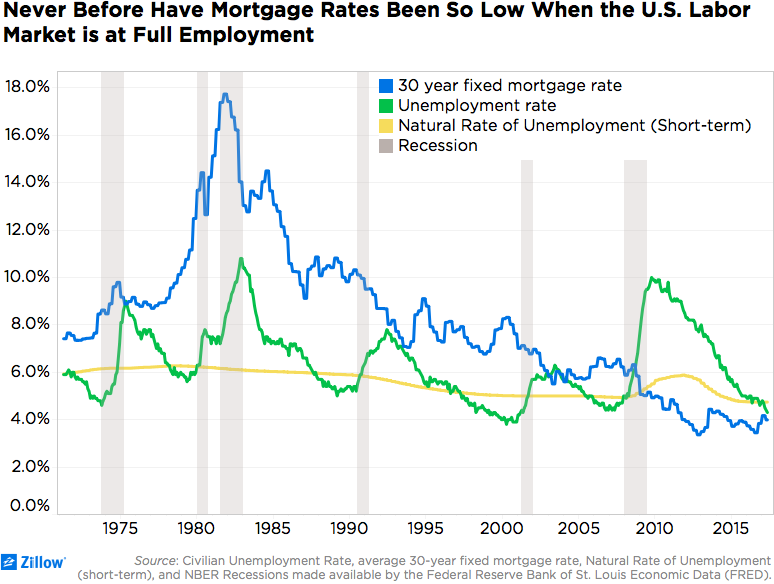

- Never before have mortgage rates been so low when the national jobs market is operating at full capacity.

- The national unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in May, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, a rate low enough to comfortably meet the textbook definition of full employment.

- At the same time, the average interest rate on a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage (the type of mortgage most commonly used by U.S. home buyers) was 4 percent, according to Freddie Mac – roughly half the prevailing rate from the past 45 years during periods of full employment.

An incredibly strong jobs market, coupled with historically high levels of home affordability, is helping create a perfect storm of home buying demand that is proving incredibly difficult for home builders and home sellers to satisfy.

In recent years, both mortgage interest rates and the national unemployment rate have each been lower at various points than they currently are. But at no point in history have both been as low as they currently are at the same time – which explains a lot about why home buying demand is so high today.

The national unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in May, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, a rate low enough to comfortably meet the textbook definition of full employment. In March, the national unemployment rate (at the time, 4.5 percent) fell below the Natural Rate of Unemployment[1] (currently 4.7 percent) for the first sustained period since late 2007. When the unemployment rate falls below this level, the labor market is determined to be at full capacity.

At the same time, the average interest rate on a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage (the type of mortgage most commonly used by U.S. home buyers) was 4 percent, according to Freddie Mac. Over the past 45 years, 30-year fixed mortgage rates have averaged around 7.8 percent during periods of full employment – almost twice the current prevailing rate.

Why Does This Matter?

For most of us, the decision on the right time to buy a home generally revolves around two key factors: Landing a steady job, and affording the monthly mortgage payments on a home. The low (and falling) unemployment rate certainly suggests the former is very achievable; incredibly low mortgage interest rates mean the latter is theoretically more possible than ever (at least in most markets), despite rising home prices.

It’s no wonder, then, that home buying demand is so high right now – in addition to expected demographic tailwinds as the enormous millennial generation ages into its prime home buying years, buying conditions themselves are mostly very favorable. Mostly, but for one small hurdle: The number of homes available for sale isn’t nearly enough to satisfy this huge home buying demand. And inventory isn’t just failing to keep pace with demand, it’s actually falling precipitously.

There are a number of reasons why inventory is low, including a lack of new construction relative to historic levels, Americans moving less and would-be sellers reluctant to list their homes for sale for fear of not being able to find another home to buy and move into once they do. It’s clearly time to add “incredibly favorable economic (if not practical) buying conditions” to that roster.

When the labor market reached full capacity in the past as it has now, the Federal Reserve began raising key interest rates, and they’re pursuing a similar course today. This will (at least in theory) generally have the effect of pushing mortgage interest rates up, lessening home affordability somewhat and potentially cool the rampant demand from home buyers. But currently, unlike in years past, these benchmark rates are being raised from historically low levels, and mortgage interest rates themselves likely have plenty of headroom to grow before affordability suffers meaningfully enough to dent demand.

In other words, don’t expect this demand to cool anytime soon, absent a massive shock to the jobs market that might cause unemployment to surge – which nobody wants.

Related:

[1] Also known as the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, or NAIRU