- The homeownership rate among young adults has declined steadily over the past four decades, but the decline has been driven mostly by changing family structures.

- Among married couples where both spouses are employed full-time, and among single young adults with a full time job, the homeownership rate is above historical levels.

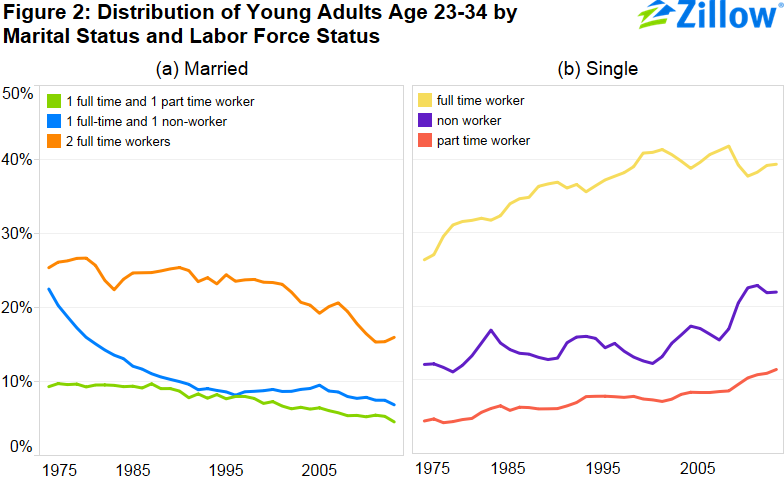

- The homeownership rate among married couples where one spouse works and the other does not—the traditional family structure—has declined steadily since the 1970s.

There has been substantial speculation in recent years that young adults are increasingly losing interest in homeownership, perhaps driven by psychological scarring from the housing crisis or due to a perceived preference for urban living.[1] Indeed, the homeownership rate among young adults has trended steadily downward over the past four decades (Figure 1).[2]

However, the aggregate homeownership rate masks more subtle demographic and labor force trends. When we control for marriage and labor force participation, and exclude young adults who live with their parents or other relatives when they do not pay rent, demographic forces clearly explain the largest part of the downward movement in homeownership among young adults.[3] Several trends are noteworthy:

- The homeownership rate among married couples where both partners work full time—the typical “modern” family—has declined somewhat since the recession, but remains above historic levels (Figure 1a).

- The homeownership rate among married couples where one partner works full time and the other partner is unemployed or does not participate in the labor force—a more traditional family structure—has declined steadily over the past four decades (Figure 1a).

- The home ownership rate among married couples where one partner works full time and the other works part-time closely tracked the homeownership rate among couples with two full-time workers, but has fallen somewhat more over the past decade (Figure 1a).

- The homeownership rate among single young adults who work full time is well below the homeownership rate among married couples, but has trended upward over time and has been roughly flat over the past decade (Figure 1b).

- There is essentially no difference in the homeownership rate among young adults who are single and either work part-time, or are unemployed or not in the labor force (Figure 1b).

It is particularly striking that among young adults who find full-time employment, the homeownership rate has generally trended upward over the longer history regardless of marital status.

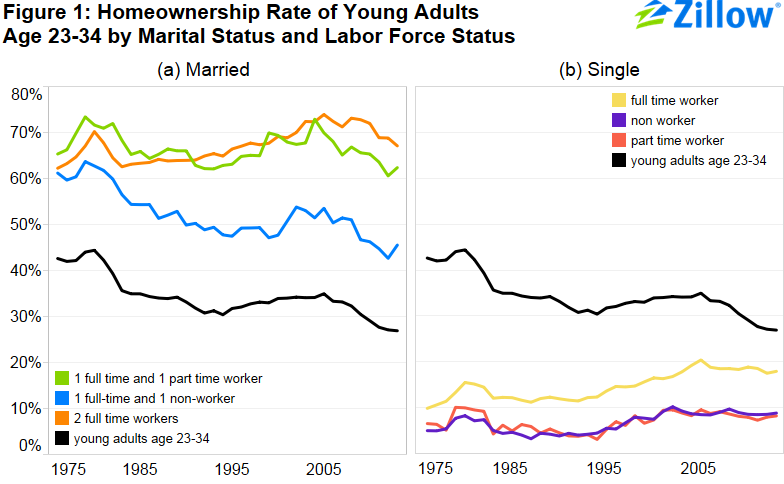

If this is the case, then what is driving the aggregate homeownership rate downward? The distribution of young adults across these marriage and labor force participation groups has also evolved over time and the shift toward a greater share of unmarried young adults has driven the overall homeownership rate downward since unmarried individuals are much less likely to own a home than married individuals (Figure 2).

- The share of young adults who are single but employed full-time (a group with a low, but rising homeownership rate) has grown dramatically from about 25 percent in 1976 to around 40 percent in 2013.

- By contrast, the share of young adults who are married where both partners work full time (a group with a very high homeownership rate) has declined from about 25 percent in 1976 to about 15 percent in 2013.

- Since the recession, the share of single young adults who are either unemployed or not in the labor force (a group with, understandably, a very low homeownership rate) has also increased dramatically—surpassing in 2009 the share who are married with two full time workers.

- Similarly, the share of young adults who are single and work part-time—another group with a low homeownership rate—has increased strongly since 2008.

- The share of young adults who are married where one partner works full time and the other is unemployed or does not participate in the labor force, and the share who are married where one partner works full time and the other works part-time—both groups with high although declining homeownership rates—have both declined steadily over the past four decades.

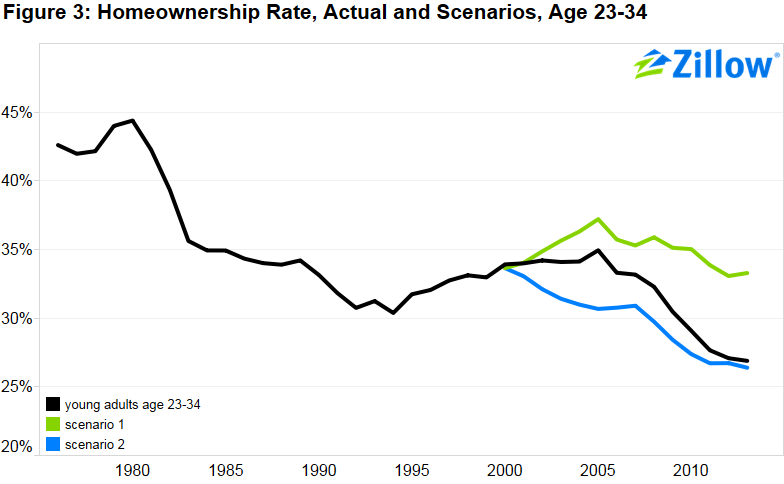

These data make it clear that changing household structure has played an important role in driving the aggregate homeownership rate among young adults. When we simulate how the homeownership rate would have evolved if household structure had not changed over the past decade, we find that changes in the distribution of young adults across marriage and labor force participation groups accounts for essentially all of the change in the aggregate homeownership rate since the year 2000.

For example, if we assume that the household structure choices of young adults had stayed the same as in the year 2000 and homeownership rates for each of these groups had evolved as they did, the aggregate homeownership would be about 33 percent rather than 27 percent (scenario 1 in Figure 3). By contrast, if the inverse were true—if the homeownership preferences had been the same as in the year 2000 but the household structure decisions among young adults had evolved as they did—then the homeownership rate would be roughly where it currently lies (scenario 2 in Figure 3).

These findings reinforce our earlier research using data from Zillow’s Housing Confidence Survey, which shows that the vast majority of young adults expect to buy homes eventually and have traditional views on homeownership.

[1] This analysis focuses on young adults aged 23 to 34.

[2] Zillow analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March Current Population Survey (CPS) made available by Miriam King, Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Sarah Flood, Katie Genadek, Matthew B. Schroeder, Brandon Trampe and Rebecca Vick, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 3.0 [Machine-readable database], Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2014.

[3] We count as “married” young adults who live with an unmarried partner.