On Thursday, May 7, Zillow will visit Detroit as part of its Housing Roadmap to 2016 series of events and roundtables.

The housing issues Detroit faces are both familiar to dozens of struggling cities nationwide, and utterly unique to the Motor City. Leading up to our May 7 visit, we will be posting a series of research pieces diving in to these complex issues. We hope to shed light on the challenges, but also to illuminate what makes the city so unique and glean potential lessons from which other struggling cities may be able to learn.

Below is the second in this series. Our first analysis, on mortgage application and denial rates, can be found here.

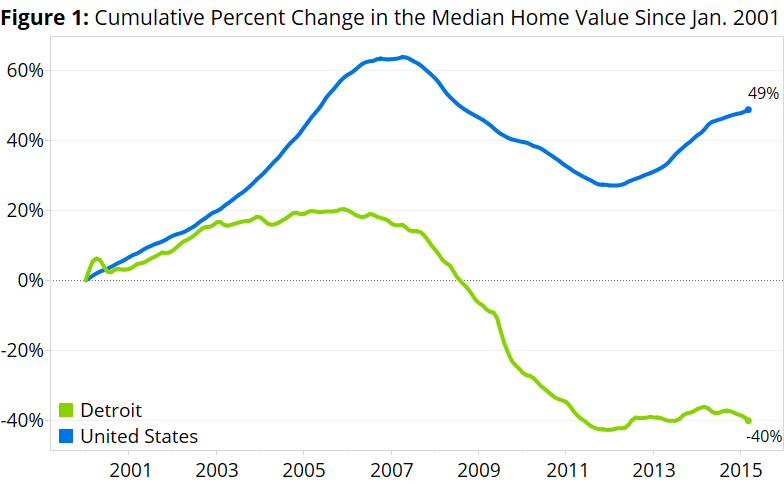

Compared to the United States overall, Detroit missed out on the mid-2000s housing boom, had a harder bust and has had almost no recovery in home values since. This helps explain much of why the city is struggling with a negative equity problem the depth of which is virtually unparalleled.

During the mid-2000s U.S. housing boom, the city of Detroit never quite got in on the action, with home values remaining largely flat even as they exploded in the rest of the country. But the lack of frenzy in good times did not protect Detroit from the bad times, with the subsequent national collapse in home values hitting Detroit as hard as any market, if not harder. And since then, while local housing markets around the country have gradually dug themselves out, Detroit has been stuck.

U.S. home values fell 22 percent from their April 2007 peak to their trough in late 2011 and early 2012, and have since risen 17 percent off the bottom. But Detroit home values fell more than 50 percent from their December 2005 peak, and have only increased about 5 percent from their trough (figure 1).

U.S. home values fell 22 percent from their April 2007 peak to their trough in late 2011 and early 2012, and have since risen 17 percent off the bottom. But Detroit home values fell more than 50 percent from their December 2005 peak, and have only increased about 5 percent from their trough (figure 1).

The near total lack of recovery in Detroit home values is one of the keys to understanding why negative equity – the share of homeowners that are underwater, owing more on their home than it is worth – remains such a huge issue in the city.

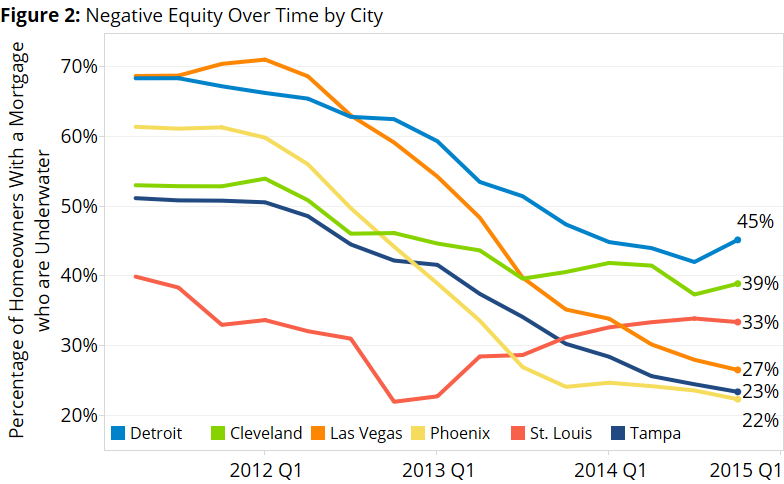

Almost half of all homeowners with a mortgage in the city of Detroit (45.2 percent) are underwater. This is a higher share, although not dramatically higher, than nearby cities including Cleveland (38.9 percent), Milwaukee (38.9 percent) and Chicago (31.5 percent). And while high, the negative equity rate in Detroit is not the highest among large American cities: Among the largest 250 U.S. cities, Hartford, Connecticut (61.3 percent), and Newark, New Jersey (45.8 percent), both had higher negative equity rates at the end of 2014.

And the negative equity rate in Detroit has fallen in the past three years from its recent high of 70 percent in Q3 2011, and fairly quickly – much more rapidly than it has in Cleveland, for example (figure 2). But compared to other cities that also had very high negative equity rates a few years ago, including Las Vegas and Phoenix, the negative equity rate has remained stubbornly high. In 2011, the negative equity rate in Detroit and Las Vegas was virtually identical. Today, the negative equity rate in Las Vegas (27 percent) is almost half the negative equity rate in Detroit. Similar trends hold true in Phoenix and Tampa.

And the negative equity rate in Detroit has fallen in the past three years from its recent high of 70 percent in Q3 2011, and fairly quickly – much more rapidly than it has in Cleveland, for example (figure 2). But compared to other cities that also had very high negative equity rates a few years ago, including Las Vegas and Phoenix, the negative equity rate has remained stubbornly high. In 2011, the negative equity rate in Detroit and Las Vegas was virtually identical. Today, the negative equity rate in Las Vegas (27 percent) is almost half the negative equity rate in Detroit. Similar trends hold true in Phoenix and Tampa.

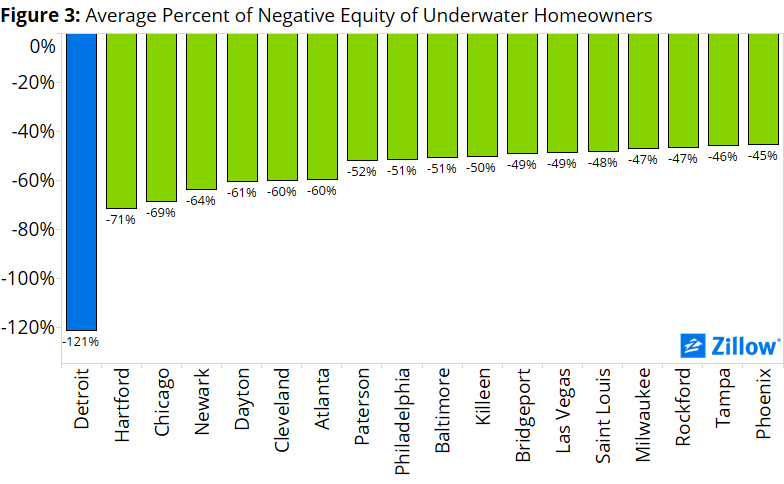

But more than the sheer numbers of borrowers in negative equity, the depth of negative equity in Detroit is what is truly harrowing. Among underwater homeowners, the average borrower is 121 percent underwater in Detroit. So, even if home values were to magically double overnight, these borrowers would still be deeply (more than 20 percent) underwater.

This depth of negative equity truly sets Detroit apart. Detroit homeowners in negative equity are much deeper underwater than other large cities, even those cities in which the overall negative equity rate is higher. The cities of Hartford (71 percent), Chicago (69 percent) and Newark (64 percent) all boast lower depths of negative equity among underwater borrowers (figure 3).

This depth of negative equity truly sets Detroit apart. Detroit homeowners in negative equity are much deeper underwater than other large cities, even those cities in which the overall negative equity rate is higher. The cities of Hartford (71 percent), Chicago (69 percent) and Newark (64 percent) all boast lower depths of negative equity among underwater borrowers (figure 3).

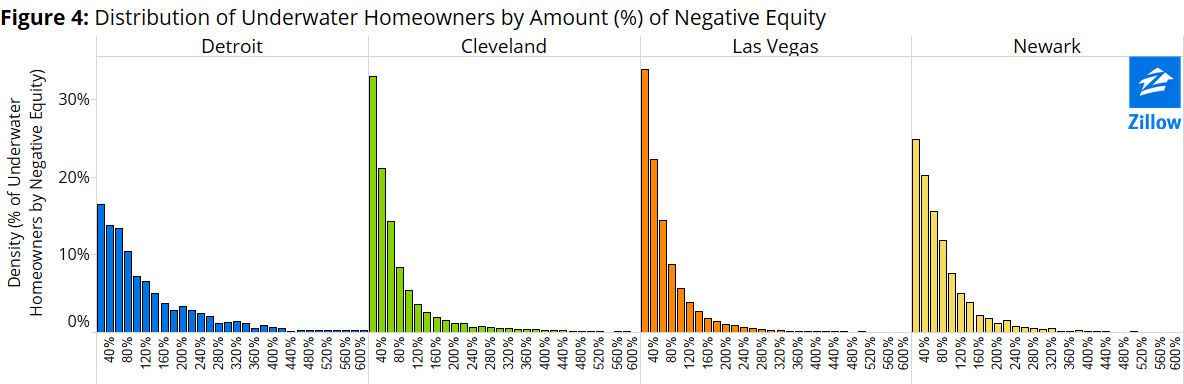

Even in other cities with widespread negative equity challenges – Cleveland, Las Vegas and Newark, for instance – many more homeowners are closer to getting back above water, even relatively speaking, than in Detroit. While virtually nonexistent in these other cities, the share of homeowners in negative equity by 200 percent and even 400 percent (owing four times or even eight times their home’s value) remains sizeable in Detroit.

And the future does not bode well for Detroit’s underwater homeowners. There are, traditionally, four ways for a homeowner to get clear of negative equity: Wait for home value appreciation alone to lift a home’s value back into positive equity; arrange for a short sale, in which the lender agrees to a selling price for the home that is less than its outstanding mortgage balance; bring cash to the closing table to satisfy any difference between sale price and the outstanding loan amount; or, cede the home to foreclosure.

Of these options, the only one in which the homeowner does not eventually lose the home or sell without profit is to simply wait for home values to rise. This is especially viable for those who plan to remain in the home for a while, and those who are not very far underwater to begin with. It also assumes that home values are, in fact, growing or expected to grow in a given area, which they are in a majority of areas.

But not Detroit.

Detroit is one of seven of America’s largest 250 cities in which home values are expected to fall through Q1 2016. And continuing its string of dubious superlatives, Detroit home values are expected to fall the most – by far – of any of these seven cities. Detroit home values are expected to drop by 3.4 percent over the next year, roughly twice the decline as nearby Flint, Michigan (1.7 percent), the city with the second-highest expected decline in home values among large cities on the list.

Essentially, for underwater homeowners in Detroit, the road back to positive territory is not only incredibly long, but it’s also likely to get worse before it gets better.

If it ever does.