- Between 2000 and 2010, the city of Denver aggressively added homes, averaging nearly one unit for every new adult in the city during that decade.

- The city’s current proposal is to build 6,000 units over the next 10 years, or about one new unit for every twenty new adults the city expects to see in the coming years.

- Denver looks to have adequate housing supply going forward, though affordability could continue to suffer while the city waits for new supply to come on line and adjust to the population’s needs.

Denver’s rapid growth has given rise to increasing concerns over both the availability and affordability of housing in the city itself. In response, the city has developed plans and proposals to try to ensure enough housing while also keeping housing cost burdens manageable. But do the city’s current plans go far enough? Yes and no.

In the coming decade, the city looks to be on track to provide enough housing to meet demand – and if it doesn’t or can’t, the city’s more immediate suburbs will likely be able to pick up some slack. But affordability may nevertheless continue to suffer, and it will take time for the market to regain balance.

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Zillow compared the city’s prior housing and population growth to current and past plans for development in the city of Denver.[1]

Past Performance

At the turn of the 21st century, Denver aggressively responded to the changing needs of the city. In 2000, then-Mayor Wellington Webb unveiled Denver’s Comprehensive Plan, describing the city of Denver as the focal point of the surrounding metropolitan area. This plan for Denver’s growth placed an emphasis on expanding and developing existing transportation infrastructure, and much of the housing built during the following decade focused on mixed-use, transit-oriented development. Mayor Webb also introduced an inclusionary housing program to help ensure an adequate supply of affordable housing, which required new projects of more than 30 units to set aside ten percent of homes for low-income families for at least 15 years.

At the turn of the 21st century, Denver aggressively responded to the changing needs of the city. In 2000, then-Mayor Wellington Webb unveiled Denver’s Comprehensive Plan, describing the city of Denver as the focal point of the surrounding metropolitan area. This plan for Denver’s growth placed an emphasis on expanding and developing existing transportation infrastructure, and much of the housing built during the following decade focused on mixed-use, transit-oriented development. Mayor Webb also introduced an inclusionary housing program to help ensure an adequate supply of affordable housing, which required new projects of more than 30 units to set aside ten percent of homes for low-income families for at least 15 years.

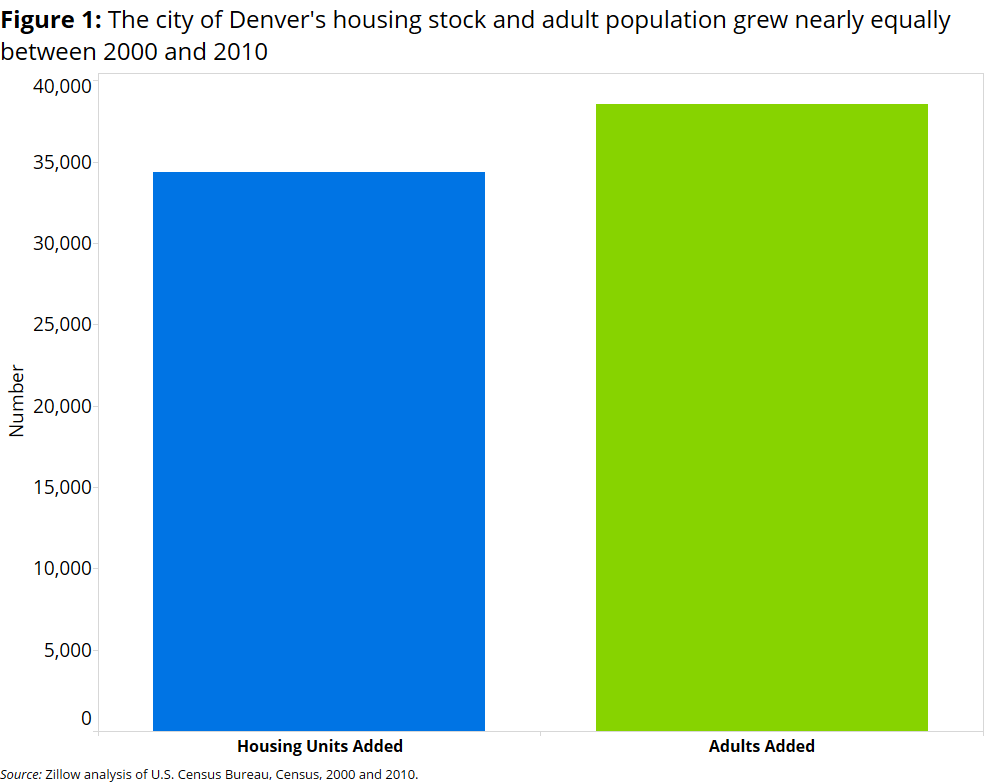

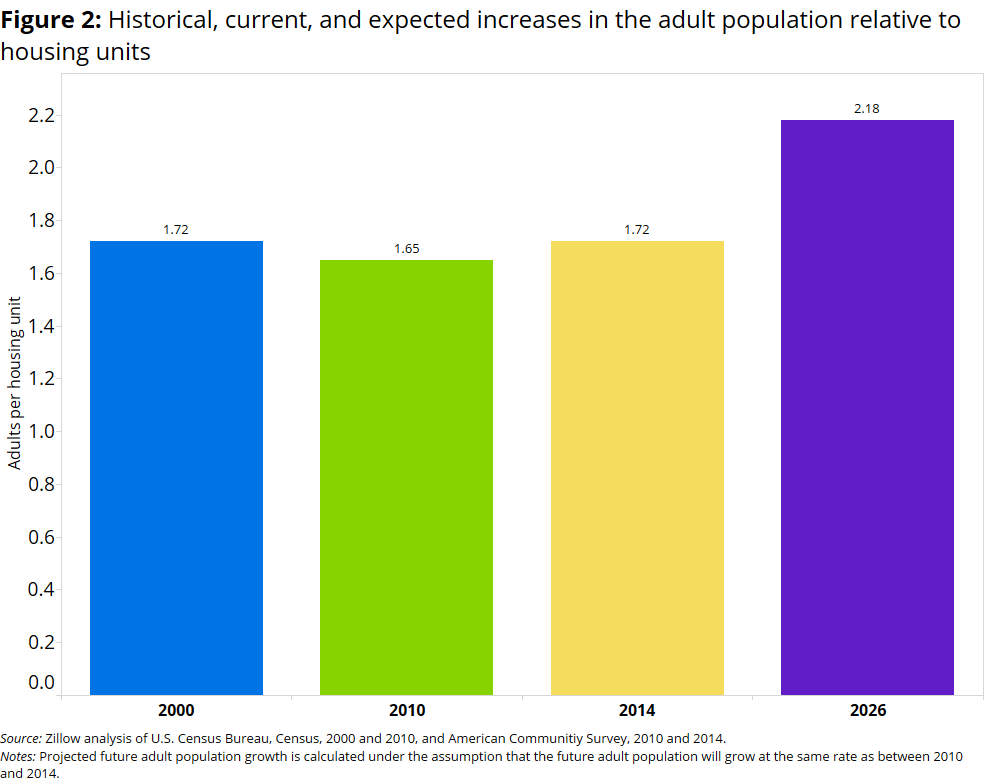

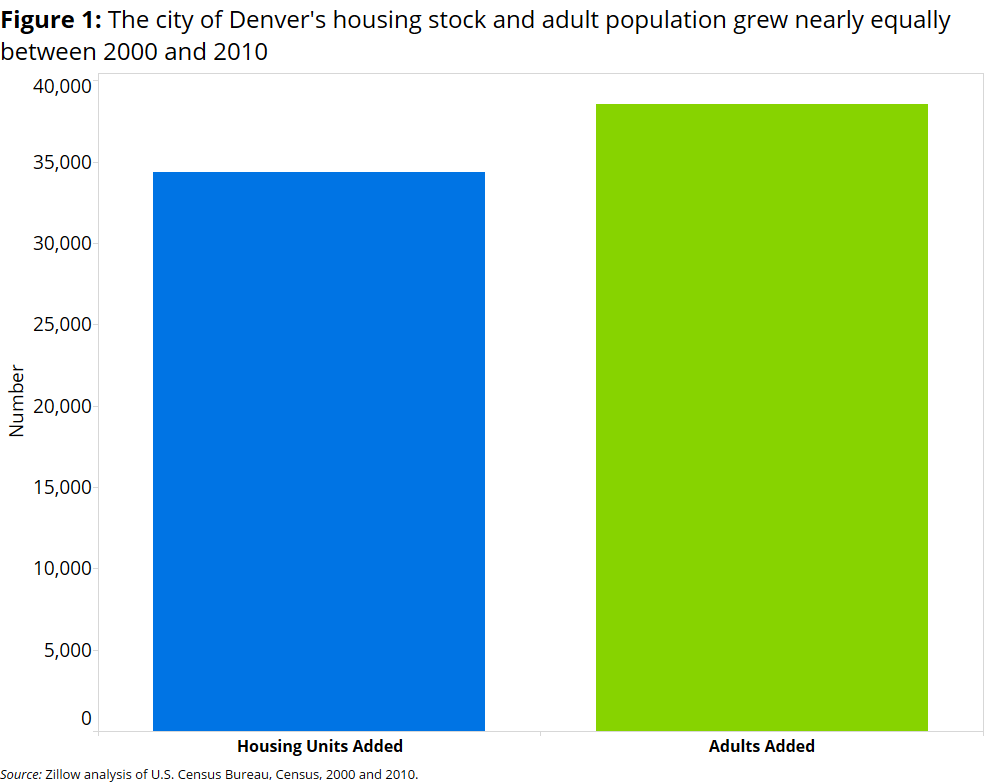

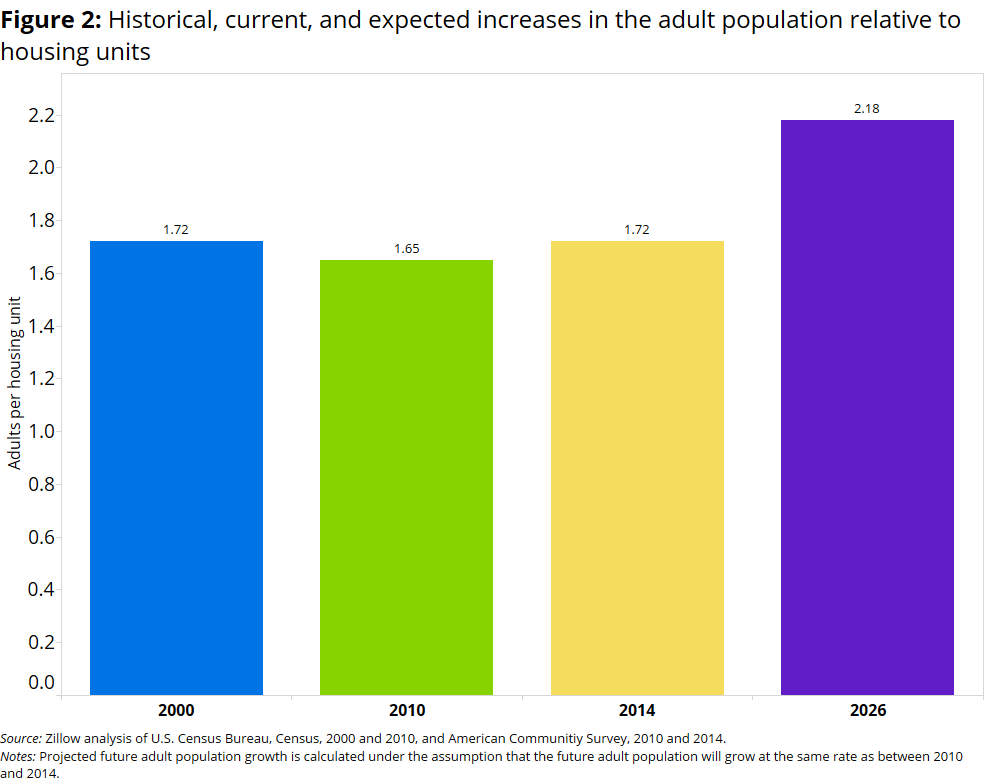

Between 2000 and 2010, Denver added 38,522 adults to the city and simultaneously constructed 34,362 housing units (figure 1), roughly one new housing unit for every new adult, a rare feat in most rapidly growing cities.[2] To illustrate just how aggressive construction was during this time, there were an average of 1.72 adults for every housing unit in the city in 2000; ten years later, despite significant population growth, the number of adults per unit actually fell to 1.65.

It is important to keep in mind that last decade’s building boom in Denver coincided with a nationwide surge in building activity during the height of the housing boom. Last decade was far from “normal” in most areas, so rather than using these results as a baseline expectation for what Denver may be able to build in coming years, this previous growth likely provides an upper bound of what is feasible for the city moving forward.

Future Returns

Looking ahead, the latest housing proposal from current Mayor Michael Hancock’s office is to build 6,000 new units over the next 10 years. At first blush, this might seem grossly inadequate given recent growth: Between 2010 and 2014, Denver’s adult population grew at a rate of 2.6 percent per year. If growth continues at that rate over the next decade, the city will need to produce about 90,000 additional units by 2026 to both satisfy new demand and maintain current housing patterns.

Looking ahead, the latest housing proposal from current Mayor Michael Hancock’s office is to build 6,000 new units over the next 10 years. At first blush, this might seem grossly inadequate given recent growth: Between 2010 and 2014, Denver’s adult population grew at a rate of 2.6 percent per year. If growth continues at that rate over the next decade, the city will need to produce about 90,000 additional units by 2026 to both satisfy new demand and maintain current housing patterns.

Under the current proposal and using the same population growth assumptions,[3] there will be about 2.18 adults for every housing unit in the city itself (figure 2). This may seem like a steep increase from prior years, and it is, but this ratio of adults to housing units is actually more or less the norm in America’s large and fast-growing cities.

It is also likely that the current proposal will not be the only housing goal set over the next ten years. For example, the city is currently in the process of executing its 2013 3×5 Initiative, with a goal of producing 3,000 units of affordable housing over five years.

Finally, Denver is and always has been one city in a larger, growing metropolitan area (albeit the area’s largest and most important city). As in years past, the city’s current housing plans and proposals consider the surrounding area’s importance in the decision-making process for managing growth in the city itself. The Greater Denver metro area as a whole has been aggressively permitting multifamily homes, meaning there will likely be enough housing units to meet the needs of present and future residents.

But the question remains whether or not residents will be able to afford them.

Match Game

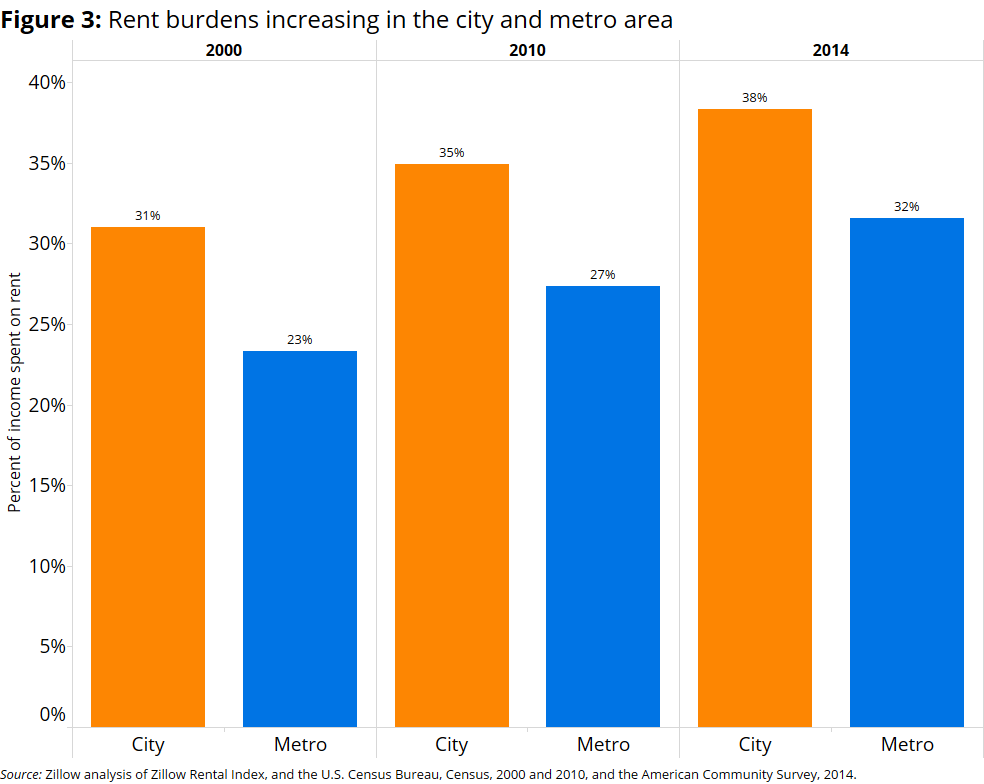

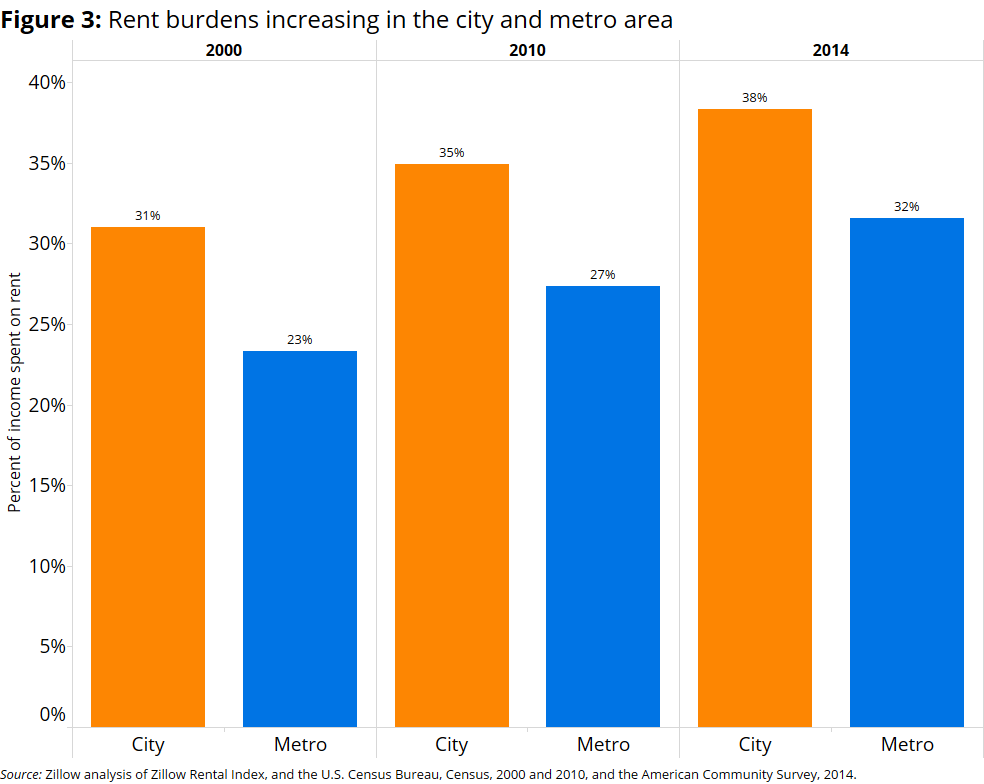

The lack of affordable housing options within the city and some of the surrounding suburbs has received national attention lately. A lack of housing supply in the face of strong growth and the demand that comes with it is typically one of the main drivers of the kind of rapid growth in home prices and rents Denver has seen the past few years. But the healthy supply of existing housing in the area, combined with ample planned construction, should theoretically be enough to meet demand. So why are local residents – particularly renters – in both the metropolitan area as a whole and the city itself spending an ever-larger share of their income on housing (figure 3)?

The lack of affordable housing options within the city and some of the surrounding suburbs has received national attention lately. A lack of housing supply in the face of strong growth and the demand that comes with it is typically one of the main drivers of the kind of rapid growth in home prices and rents Denver has seen the past few years. But the healthy supply of existing housing in the area, combined with ample planned construction, should theoretically be enough to meet demand. So why are local residents – particularly renters – in both the metropolitan area as a whole and the city itself spending an ever-larger share of their income on housing (figure 3)?

One possible reason may be that those homes that are available are not a perfect match for the population. Prior to 2014, Denver had more homeowners than renters. Today, renters make up a small majority of all households. Since the majority of homes were owner-occupied until very recently, the type of housing constructed over the past 15 years may not align well with the preferences of renters. For example, single-family homes account for roughly 53 percent of the city’s homes, but as of 2014, 74 percent of the city’s renters lived in multifamily homes. Additionally, recent research suggests that newly built homes are both denser and more expensive. Whether this is driven by residents’ preferences or builders’ desire to maximize profits is unknown, but the effect is clear: higher-end homes cost more, to both buy and rent.

Compounding this potential mismatch is the possibility that despite the city’s efforts to expand affordable housing, it is simply not enough. Wages have been largely stagnant for the past decade, while home values and rents have rapidly grown. This would put pressure on any housing market, including Denver’s, which could be leading to this short-term imbalance.

Compounding this potential mismatch is the possibility that despite the city’s efforts to expand affordable housing, it is simply not enough. Wages have been largely stagnant for the past decade, while home values and rents have rapidly grown. This would put pressure on any housing market, including Denver’s, which could be leading to this short-term imbalance.

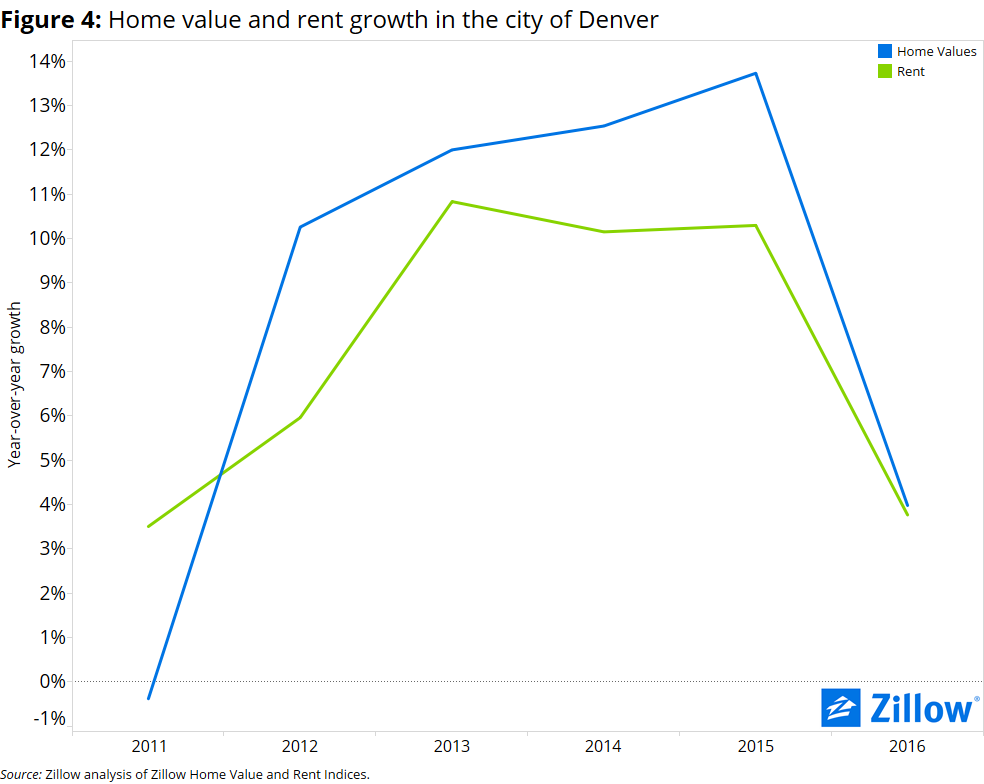

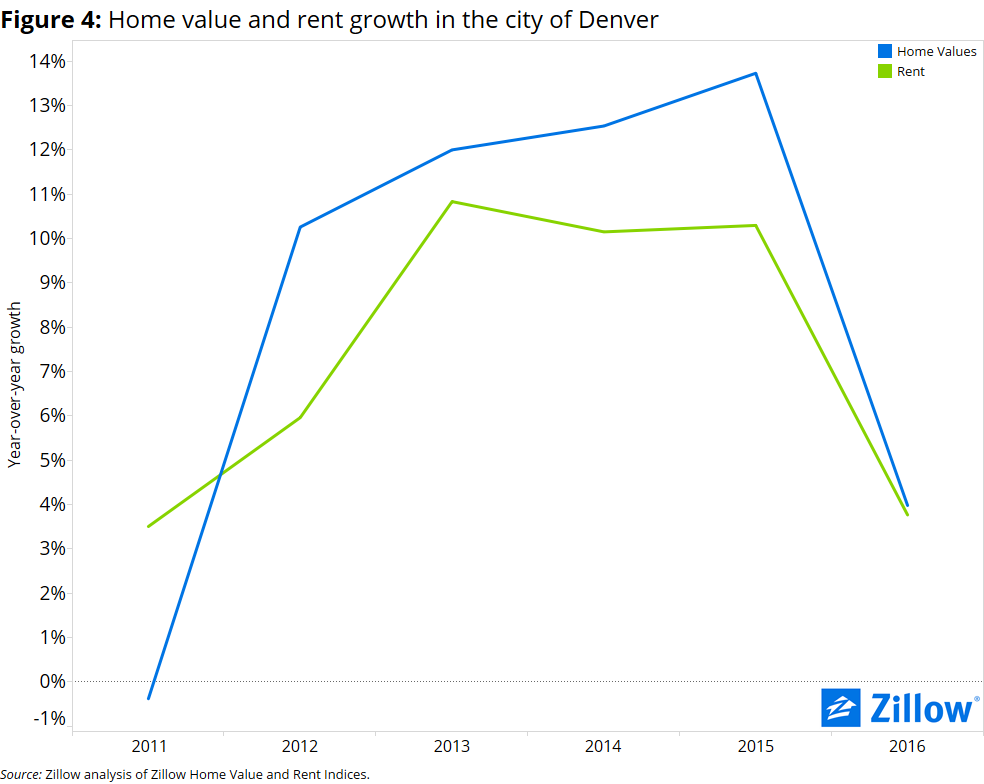

But growth is slowing, and expected to continue to slow (figure 4). In 2015, home values in the city of Denver rose 13.7 percent. By the end of 2016, Denver home values are expected to grow just 3.9 percent. Similarly, rents in the city – which grew 10.3 percent year-over-year as of the end of 2015 – are expected to grow 3.8 percent through the end of this year.

The slowing growth, alongside a booming economy, indicate that in the long-run, Denver’s housing market may yet iron itself out.

On March 30, Zillow will make Denver the seventh stop on its Housing Roadmap to 2016 tour of America, aimed at discussing housing challenges in the cities most impacted by them. Over the past decade, Denver has become one of America’s fastest-growing cities, with droves of new residents attracted by the city’s legendary beauty and quality of life, and its abundant job opportunities.

But growth does not come without growing pains, and Denver is not immune. Prior to our March 30 discussion, Zillow will publish new research detailing the factors driving Denver’s enviable growth, as well as some of the side effects.

We invite you to please tune in on March 30 to the live-streamed program at: http://www.zillow.com/housing-roadmap/denver

The program will begin at 12:45 PM MT/2:45 PM EST.

[1] We assume that when a housing development plan involves “preserving”, “rehabilitating”, or “restoring” housing units, then these units would have otherwise been demolished or would no longer part of the housing stock within a city. We further assume that every unit constructed is a unit added to the housing stock. In other words, construction does not also involve the demolition of other units.

[2] We compare the housing stock growth to adult population growth because adults are ultimately the ones demanding housing units (and paying rent or a mortgage). A significant increase in the average number of adults per housing unit may imply that the city is not keeping up with demand. For example, in many large and fast-growing cities, an emerging trend is for unrelated adults to live together in order to combat high rents and home values.

[3] The assumption is that the population will continue to grow at the same rate as between 2010 and 2014. While this is imperfect, it serves as a rough ballpark, as the city shows no signs of slowing population growth in the coming years.